by Luis Amate Perez

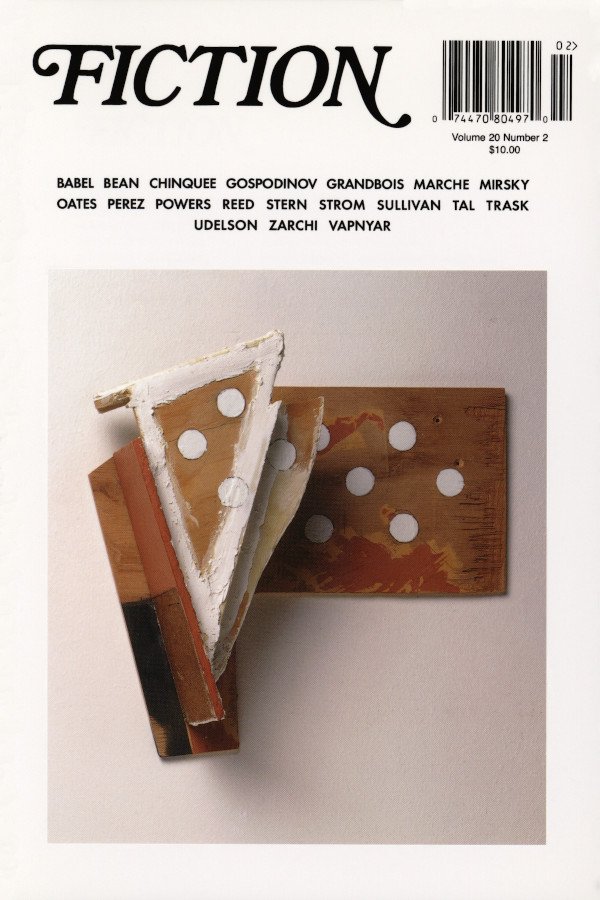

From Fiction Volume 20, No. 2 (2007)

SHE COULD HAVE been a boy. Her chest looked stripped of the fat and muscle that make breasts possible. Although this was the first time I'd seen her topless, I felt as though I'd seen her bones somewhere before, in the mirror over my bathroom sink after a bath—the chest of a bony nine year old boy—a reflection.

I was covered, wearing Tony Amonte's New York Rangers away jersey: number 33, a portion of the back tucked into my sweats over my left hip, the ends of the sleeves hidden inside my blue Koho hockey gloves. Even with the rollerblades on and the sturdy stick in my hands, I was no bigger than the other guys. So, when they told me to translate the next move into her Spanish, I did:

"Now, take off your pants."

I didn't want to share my room with Florencia. Not because she was a girl; by the second grade I'd already wracked up a number of girlfriends: Natasha Lynn, Cynthia Marie, and Grace Leigh—to name three. Nothing major—although these were the serious relationships—a little handholding, but mostly just something to call each other—and get teased for—on the playground. You're my girlfriend. He's my boyfriend.

In the third grade I took the plunge and proposed marriage to Tiffany Rogan. I waited for a "Yes" that whole afternoon, but instead of giving me an answer she got diarrhea, and her mother had to come pick her up from school. Tiffany was absent for the next month.

Now it was the fourth grade, and every day for a minute—no more—in the stairwell on our way to the cafeteria, Ciara Parker, a kind, fat mulata with freckles, would let me have my way with her left thigh. No kisses. Just a bump and grind. "Does that really feel good?" she'd ask, almost always.

And at night in bed I wouldn't dream about Ciara or her faithful left thigh, but about all the other left thighs in the world and the right ones, too—and the secrets that lay between them. What was Natasha's secret? Cynthia's? Grace's? Diana Boyle's? Marybeth Eagan's? Tiffany's? Especially Tiffany, who had moved far away to East Meadow, Long Island before the start of the fourth grade, months after she'd told me that we were too young for marriage—what was her secret?

I didn't want to share my room with Florencia. Not because I was afraid she'd catch me: in the middle of the night humping my pillow, or doing it doggy style with the used and abused My Pet Monster I kept at the corner of the bed (for the times I needed to ball something with arms and a head). No, to have a girl in the bottom bunk, two years older than me—I guess, more woman than I was man—might've helped my situation. She could've given me a hint, even just audibly, of what sex might really be like: another body's tosses and turns beneath the covers, another mouth's breaths—snores, even some mumblings—pillow talk. The stuff the other guys and I never saw on Spice.

No, I didn't want to share my room with Florencia because I thought she was dirty. She wore trash. The first time I met her she was wearing my mite hockey jacket, the one I knew my mother had thrown away—why else had she put it in a black garbage bag along with all the other clothes I'd outgrown? And after my mother had introduced the two of us, having raised her voice so that Florencia would better understand the words "your cousin," she helped Florencia to strip off the first sleeve (my old jersey number and position stitched into the white pleather) and then the next sleeve (third place in our division) to reveal my discarded Edmonton Oilers T-shirt.

Now, I realize that she was not dirty, that her eyes were not the color of dirt, that I was too big for that jacket—that I no longer played right wing nor wore number 88 (I didn't play hockey anymore), that her hair was not the color of mud, that I hated the Oilers and every other team that was not the Rangers, that she spoke my father's language because she couldn't speak English—not to remind me of his absence and the words he'd never teach me. I realize that as my mother stripped her of my jacket (her jacket), as the other guys and I would strip her of the rest of her clothes, that there was more to her than my layers and the inches of dirt any boy with enough desire can cake on a woman.

But at the time I could only look at my mother and ask, "Why's she got my stuff on?"

My mother folded the jacket over the back of one of the chairs in the kitchen. "She don't got your stuff on, so don't start." She walked to the refrigerator. "Florencia, Pep-si?"

My cousin nodded like a mute and sat in the chair—sat on her hands, her thighs covered with pants that were never mine. Hunched over, her straight hair hanging past the small of her back, my jacket visible behind her head—somehow, for me, the four wooden legs and wobbly seat creaked and turned into something holy: the sepulcher of my mite hockey career?

"Now she's on my chair, Ma!" That's all I could scream; the word blasphemy was not in my vocabulary.

"What's your problem?" My mother, liter of Pepsi in hand, turned from the light of the refrigerator, her nervous tic taking over her left eye. "You gonna act like a shit? Is that what you're gonna do?"

"She's wearing my clothes—she's touching everything—"

"They're not your clothes no more—they're hers."

"She even know who's on the Oilers, Ma?"

"You keep at it, and I'm gonna smack your face—"

"Florencia," I said, knowing the smack wouldn't come. "Tell me, who's on the Oilers?"

My mother opened a cabinet door, then slammed it shut. I'm sure she was imagining my mouth busted open, my new front tooth lodged in her knuckle.

"Tell me, Florencia!"

My mother threw open another cabinet. "She don't speak English!" She slammed a cup down on the counter. "God!" She twisted the cap from the excited liter of Pepsi, sending caramel foam into the air. "For fuck's sake!" The bottle slid out of her hands, spraying as it bounced and rolled on the kitchen floor.

In Spanish I told Florencia to name all the Oilers she could—if she couldn't name them all then just one. Just one! But she sat there, face downcast. She knew she was an invader, a witness to another disturbance in a sad apartment. And I had no sympathy for her, the tan creature wearing my old T-shirt; all I had was the 1992-93 Edmonton Oilers' roster:

"Uno: Bernie Nicholls," I began. "Dos: Craig Simpson. Tres: Geoff Smith . . . ."

"Shut up! Shut up!" spilled from the floor. My mother was on all fours wiping up the soda with a paper towel. "Please! Shut up!"

" . . . . Cuatro: Shayne Corson. Cinco: Craig Mactavish . . . ."

My father had been dead three months. The Rangers wouldn't even make the playoffs that season. My mother was crying again. I wouldn't stop:

"Seis: Petr Klima. Siete: Bill Ranford. Ocho . . . ."

I was one of the first to get rollerblades, before they were popular; most people were still skating on quads. There was a time, I think, when I was always skating. I'd skate from J-Building to the schoolyard in back of P.S. 151, pushing the puck—a disc of electrical tape—ahead of me, losing it in the grass or the gutter, then digging it out again. People thought I'd play for the Rangers one day, just because they always saw me skating.

Weeks before she'd arrived—two months after the funeral—people had already stopped patting my shoulder or wrapping me up in it's-gonna-be-okay arms. Even Ciara, during our nooners on the stairwell, had stopped resting her hands on my shoulders and telling me, "I hope you feel better." I know those short weeks of change were important: her plump fingers resting near my neck, a flake of dried Elmer's Glue caught in the webbing of her hand, waiting to be picked at the lunch table. I bet from the top stair it had looked like we were slow dancing.

I'd stopped skating around the time Mikey'd discovered the gifts of illegal cable. Now every day after school there'd be Spice, and on special occasions the magic box would give us The Royal Rumble andWrestleMania. On the special occasions we'd argue over how real professional wrestling was; none of us had ever gone so far as to call it a complete sham: we'd see the Macho Man go off the top rope and deliver his "Savage Elbow" to some dude's head, but we'd also count the hits that never came close enough to inflict the pain they caused. With wrestling we'd always be adding up our doubts and certitudes—we'd always break even. But with porn it was different: we couldn't deny the way it made us feel. We could clothesline and body slam each other all we wanted, but we couldn't do that. That was impossible. Even for Walter, eleven years old—the oldest. All we could do—Mikey, Johnny, Walter and me—was lie there next to each other on Mikey's parents' bed and watch.

The first time Mikey'd flipped the channel we witnessed Nina Hartley go face first into Peter North's lap. We didn't want to miss any of it—but how could we? With the three repetitious camera angles: a closeup of Nina's eyes looking into the camera lens (from Peter North's point of view); a wide shot—the back of her head bobbing up and down, as Peter North made these faces; and a medium shot from the side of the couch where an out-of-focus vase hid the oral.

I still have no idea why Spice cut the footage like that, why they made sure any trace of cock or penetration was buried behind inanimate objects and awkward jump cuts to a painting on the wall or to the profile of a male star; perhaps it was a punishment for the Time Warner thieves. Anyway, it was real; we knew it from day one.

"Trust me," Mikey'd said, a pillow draped over his lap, "she got his dick in her mouth."

There's footage somewhere of my tenth goal—my father did the counting. You can hear his voice peak on the video tape: "That's number 10!" In the middle of a grainy Christmas scene (tinsel, a fully assembled roller hockey net, presents, an obstructed tree) we cut to a grainy ice rink (my team pats my helmet and shoulders, the Arrows goalie bangs his stick, and my father counts out loud), and then we cut back to Christmas: I'm trying to lift the net, I want to skate.

"I want to skate," I say.

My mother says, "You haven't opened up all your presents yet."

My father, behind the camcorder: "Let him skate. Let the kid skate."

I tried to "avoid" Florencia—had I ever used that word, that's what I would have called it at the time. But how could you really avoid her?—in a two-bedroom apartment. In reality I was just keeping my distance, watching her movements from behind the doorjambs, listening in on her long-distance calls to Tucumán—missing the words I hadn't been taught—and hearing about how much she hated it all, this apartment and this country.

I let my mother struggle to explain things to her, but she managed to lend Florencia a few English words. During dinner it was "Butter"—always "más Butter," piles of it, a meal of it. And after dinner it was "Bathtub"--"Yo voy al Bathtub." I'd keep an ear cocked, to make sure she wasn't messing with anything in the bathroom—that after she'd left it, wrapped up in my towels, the Bathtub was still there, drunk on her bathwater.

In class I managed to keep imaginary tabs on her. She didn't have to go to school, because this was supposed to be her vacation, a month in New York with her Uncle and his American family. The tickets had been bought before my father died, before I'd imagined her creeping through my closet and drawers, rubbing my wears all over her bathed body. To be sure it was just fantasy I'd sniff the clothes later in the day, trying to catch her smell—the scent that exhausted the pillowcases and sheets on the bunk below me. I'd sometimes have to tear the sheets from the mattress and pull the pillows from their slips. My mother would always remake the bed.

There was still Mikey's parents' bed and the few hours of edited sex. But after a little over a month's worth of captivation it seemed as though Spice had run out of programming.

"This is bullshit!" Walter said, taking up a full side of the bed. "They play the same shit every day!"

"I don't know," Mikey said. He stuffed some Doritos in his mouth. "I don't know what's up with it."

"I'm gonna try to piss," Johnny said, then left the room holding his groin.

"God I hate this guy!" Walter stood up and walked to the armoire with the television on top of it. He jumped and smacked the television screen; the man's black coif didn't move.

"Are you crazy?" Mikey said with a mouthful of chips. He struggled to swallow the orange paste in his mouth. "You're gonna break it!" He sucked the spicy powder off his thumb.

"Now what's he gonna do?" Walter said, staring up at the scene. He reached back and took a pillow from the bed. "He's gonna bend her over like this." He folded the pillow in half like a book and positioned himself behind it, his crotch in line with what would've been the pillow's spine. "Now what? Right in her ass: Bam! Bam! Bam!" He thrust his pelvis into the pillow, keeping time with the bucking porn star—both of them oblivious to the rhythm of the soundtrack backing the scene. "What's he gonna say now? Come on, say it."

"Let me see that pretty face!" Mikey and I responded, our lips in sync with the closeup of the male porn star's face.

Johnny reentered the room, tugging at his junk, and without warning Walter grabbed him around the waist and tossed him onto the bed facedown. Mikey hopped onto the bed and held Johnny's outstretched arms against the mattress.

"I can't breathe," he squirmed. "Asthma, assholes! I got asthma!"

"Let me see that pretty face!" Walter said, securing Johnny's kicking legs.

"Let me see that pretty face!" Mikey added. "Come on!" He looked at me—I was out of bed and close to the door by now. "Don't you wantta see his pretty face?"

"I'm gonna piss the bed!" Johnny screamed.

"You better not!" Mikey patted Johnny's face, leaving streaks of orange dust on his hot cheeks. "Then you won't get that raise."

"'Oh, you're gonna get that raise, baby'!" Walter said, dry humping Johnny's backside. He gave up kicking. "'I can just see that check now.'" Walter turned to me. "Can you see it? Can you see it?"

The scene had already ended on the television, having dissolved to a parking garage. The limo had no driver, and the two women going at it on the black hood were not shy. In a couple of seconds a man strategically placed behind an oil drum would snap a photo of the naked yet gartered business women, who were so intoxicated with one another that they couldn't see or hear the flash.

"Yeah, I can see the check," I finally responded.

The other guys were now all laughing on the bed, going on with their interpretation of the previous scene. I probably joined in.

Sometimes I'd dream about the building—all six stories—crashing down on our basement apartment. It wasn't a nightmare. I was safe in the dream, free from harm on the top bunk. I'd never wake up screaming or crying, I'd just look at the ceiling and try to talk it into collapsing. And when it wouldn't, I'd haggle, bidding for the deaths of Mikey, Johnny and Walter's fathers—each dead in his bed, stacked on the floors above me. "Please die," I'd ask the spirit in the ceiling. "Just once, make them die."

I could turn from those kinds of prayers—like turning over the pillow to find its cooler side—back to Natasha and Kathleen O' Connor, Grace and Rebecca Green—Little Miss Rogan. I could scratch at their unknowns, dig myself back to sleep. But that changed with Florencia. With her sleeping in the bottom bunk, tossing below me, snoring, turning, living, I was closer to the secrets—but I was by myself. The other guys weren't with me.

Sure, I used to skate alone—Walter, Mikey, Johnny, none of them played hockey. None of them skated in the back of P.S. 151 (the public school I attended) when ice time wasn't available. But there wasn't much mystery to skating, practicing your crossovers, strengthening your wrist shot against the walls. There was nothing mysterious about one day playing for the Rangers. You just had to keep skating. And on the weekends when your father drove you out to the Island—exits, you'd one day learn, past East Meadow and Tiffany Rogan—to play a game, and you scored, you knew that you didn't have to keep count, because he was already doing it for you, logging it for eternity on a grainy piece of video, the montage that is your childhood.

What do you do when he's no longer there to count for you?

Well, first you try to remember each goal he was there for—the assists too, and the penalty minutes, the timeouts—and then you try to replay them, except now you're not on the ice, you're on rollerblades in the schoolyard, slapping a slab of electrical tape past an invisible goalie from the Arrows. But when the puck finds a way between the goalie's pads and hits the back of the net, and your team pats your shoulders and helmet while the Arrows' goalie cracks his stick on the ice, you know that it's not really number 10. It's not even a goal. It's like watching some body come in a porno.

So, you hide your skates—ice skates and rollerblades—your stick, your gloves, your puck and your favorite hockey jersey—you put everything but the stick in your big hockey bag—in the back of your closet where you'll try not to find it.

She could have been a boy. Just cut that long, pretty hair of hers—I can see it now—and put my Edmonton Oilers T-shirt back on her. Put her jeans back on . . . .

"Tell her," Walter said.

I pretended to search for the word and prayed silently into my blue Kohos that I might never find it. But before I could stall the inevitable any longer they were down around her ankles.

"Panties?" she said.

I had tried to keep her a secret. But we all lived in the same building: Mikey on the sixth floor, Johnny on the fourth, Walter on the second. The apartment building made us intimate; it stacked us on top of each other. Lying between Johnny and Walter on the bed—Mikey at our feet—I, having minutes before upended Florencia's bunk and entangled myself in her sheets and pillow cases, I knew it was just a matter of time before they caught a whiff of her. And every time they turned to me and smiled I should have known that they were really looking at her, the girl they hadn't met yet, the girl (I now realize) I'd shared so many features with: we both had my father's eyebrows, thick and black—my mother had pointed them out—and deep clefts in our chins, and lips that seemed to be hiding. I didn't want to share her.

Then, one Wednesday, Saint Joseph's let Walter, Johnny and Mikey out early. They sat around the table in my kitchen, uniformed: khaki pants, polite, black shoes, charming, and white short-sleeve shirts. Johnny was attempting Spanish, mangling the word "miércoles." Florencia sat blushing—of course—at the table. My mother filled their cups with Pepsi.

"There he is!" Walter said. "We came to call for you."

Spiked dirty-blond hair, all his teeth, eleven years old—Walter was handsome.

"Hola!" Mikey and Johnny said, seducing Florencia. She laughed.

At that moment, like so many other moments, I wanted to see something fall apart. Anything. I ran to my bedroom and tore the sheets from both our beds, opened the drawers and scattered our clothes all over the room. I pulled jackets and shirts off their hangers, then tossed them at the ceiling. I wanted debris and fallout. My hockey bag—no longer hidden in the closet, the curtain of clothes having been ripped from their rod.

"What are you doing?" my mother shouted, her left eye blinking hysterically.

I looked for the guys behind her, but they weren't there. They were probably still in the kitchen, prepping Florencia.

I had no answer for my mother, so I just said, "I hate it."

"Hate what?" my mother reached out to my sleeve.

I opened my hockey bag—maybe I thought I'd find an answer there—but feeling my mother's lips on my ear and her arms enveloping me, I said the first thing that should've come to my mind:

"I miss Daddy."

She could have been a boy. Except for that light trail of brown hair. We'd never seen something like that up close; it was always on the TV screen—an artificial version of it at least—two-dimensional, well-trimmed or totally bare. Not like ants scattering from their mound. What was inside it?

I wore Tony Amonte's jersey for the rest of the month, and I left Ciara's left thigh alone—the girl never even asked me what changed.

I slept with my mother in her bed and tried to dream about the Rangers.

I skated.

At night I tried to think about Mark Messier, Adam Graves and Brian Leetch, but my mind moved to Florencia in the other room and what she might be doing in her bottom bunk. I imagined her lying between Walter and Johnny on the bed, Mikey at their feet. What did she think of Spice? Had she grown tired of all the repetitions--the reruns? Was it all too fake for her?

"What does, 'No es real,' mean?" Mikey asked me, his fingertips stained orange. "She keeps saying it: 'No es real.'"

"About what?" I said, not sure why I was back there in the room with them, why I wasn't skating, why I'd knocked on Mikey's door in the first place.

"The porn," Johnny said. "'No es real. No es real.'"

"It means: it's not real."

"No!" Johnny shook his head at her. "Es real!"

"No," she laughed. She took a Dorito chip from Mikey's palm.

My hands went clammy inside my blue Kohos. I was scared that she might actually know. I gripped my stick and dug the blade into the carpet.

Then Walter said, "Hey, tell her to show us the real thing."

Let me see that pretty face.

Didn't I catch her smile?

Camiseta: the Edmonton Oilers emblem had faded more than the last time I'd seen the T-shirt on her.

She could have been a boy.

Pantalón vaquero: the new jeans my mother had just bought for her.

She could have been a boy.

Even though they were just words, I felt like I was ripping her clothes off. I wished my father had never taught me those words.

Panties?

Walter was the first to touch her, to trace the line of ants with his finger, to part her lips and enter the mound—the secret.

That night I got up from my mother's bed and snuck into my bedroom. I kneeled beside Florencia's bunk and watched her sleep for a bit.

I wanted to ask her if any of it felt good. If she was really smiling the whole time.

Now, I would have woken her up and said I was sorry, that I'd teach her to skate, if she'd let me. But at the time I couldn't.

She was very pretty.

Luis Amate Perez writes and performs for stage, film and television in addition to his fiction and poetry. He is often credited as Lou Perez. He has his BA from The Gallatin School of Individualized Study at NYU.