By Silvina Ocampo

Translated by Suzanne Jill Levine

From Fiction Volume 6, No. 2 (1980)

For Rosie

HER NAME WAS Coral Fernández; she always wore her hair over her left ear, leaving the right one uncovered. She was so pretty that at first I thought she was foolish.

We met at a country luncheon to celebrate the opening of the Cyclist's Club in Moreno. The tables were set beneath a grove of blossoming paradise trees; there was a bandstand and a floor for dancing. During the lunch we were seated next to each other. We didn't speak at first but immediately we felt mutually attracted. Love at first sight exists, without a doubt. Under the table something grazed Coral's leg, something that wasn't a scandalous leg, but a cat. Coral was startled, the two of us bent down to see what was under the table, and we laughed. At some moment I asked her to dance, and I liked her hand, and I liked to hold her, and I liked her laugh and her perfume. The sun was already sinking and we were still sitting in that place, so seduced were we by one another. A slight nausea came over me, a violent headache. I attributed it to sunstroke, although I had scarcely been in the sun. She wet her handkerchief in the pitcher of water and cooled my forehead. As I like to be pampered and she is loving, with this act an intimate friendship began. When saying good-bye I told her sincerely that from that day on a headache would bring me the most pleasant of memories: that of having met her.

Both of us used the same tactics: hiding from each other the interest we felt. For a while we saw each other only once a week, at the house of mutual friends. The house had a garden where we'd stroll, away from the people. The parties were on Sunday nights, with card games, dancing, music. We didn't need to see each other anymore to know that we got along perfectly.

"A pity I always see you the day I have my headache"—I told her to hide my emotion, because it was emotion that made my head ache and that gave me sunstroke.

"We could always get together any other day"—Coral said provocatively.

We got into the habit of meeting daily at tea shops, movie houses, squares, anywhere, even in places I won't mention. I got sick and a gloom came over my happiness. Mine wasn't any old sickness; suddenly my head would ache, or I'd catch cold, or I'd be covered with hives, or I couldn't stand up straight, or my eyes would burn. I went to several doctors, who subjected me, in vain, to blood tests, X rays. Doctors get mad at diseases they don't know. My sickness did not have a name. The doctor assured me I was healthy. I decided at once to marry and to leave, married, for Cordoba. However, for reasons of work, we were separated for twenty days. I had to make a trip to Brazil and my health improved remarkably.

I came back changed, full of energy and enthusiasm. In a way Coral scolded me for it.

"It would seem that it did you good to be away from me."

We went back to seeing each other every day, but soon my health declined and Coral again scolded me for the favorable change of spirit produced in me when I was far from her. She was jealous; jealous of her absence. We fought like two children. Finally I left with a young nephew to spend the summer in Tandil, and I told Coral that I was going to a sanatorium for nervous disorders. I wrote her letters but I kept my address from her; I gave her another so that she could answer me. I improved significantly, but when I'd take up the pen to write my fiancée, my hands would become covered with eczema. I'd get better, I'd get sick, successively. My eyes would begin to burn as soon as I'd receive Coral's letters. I asked my nephew to read them to me. I took the precaution of sitting at the other end of the room, because if I was too close to him when he read them to me, I'd feel pricking sensations in various parts of my body, especially inside my ears. My love for Coral, however, did not decline. I wrote her impassioned letters telling her that I would never see her again and that if she really loved me she'd accept without explanations. Her love for me doubled. In the letters she assured me:

"I thought about you all night, unable to sleep."

That same night I, complaining of some strange pain, did not sleep either.

"Don't think of me"—I begged her.

"Then how am I to live? It does me so much good to see you."

"Our organism doesn't permit us to be together"—I told her, feeling the ravages of her presence in a cough.

Telephonically I proposed that we have a child by artificial insemination, after marrying by proxy. The telephone conversation was brief, but the procedure was as long as it was distressing. No other woman would have accepted the difficult situation in which I had placed her before society. She accepted it with resignation. Our son had to live. We already saw his face in the most beautiful paintings; the color of his hair and his eyes, the virtues he would inherit.

From time to time, I make the sacrifice of writing to Coral, taking a thousand precautions.

From a distance I've seen our son coming out of school, but I didn't come closer to speak to him for fear that he had inherited his mother's power, which worked so terribly upon my allergic organism. I know that he has a portrait of me at the head of his bed, and the mother-of-pearl penknife from my childhood, and that, like me, his name is Norberto; that he has inherited his mother's profile and his father's knack for drawing.

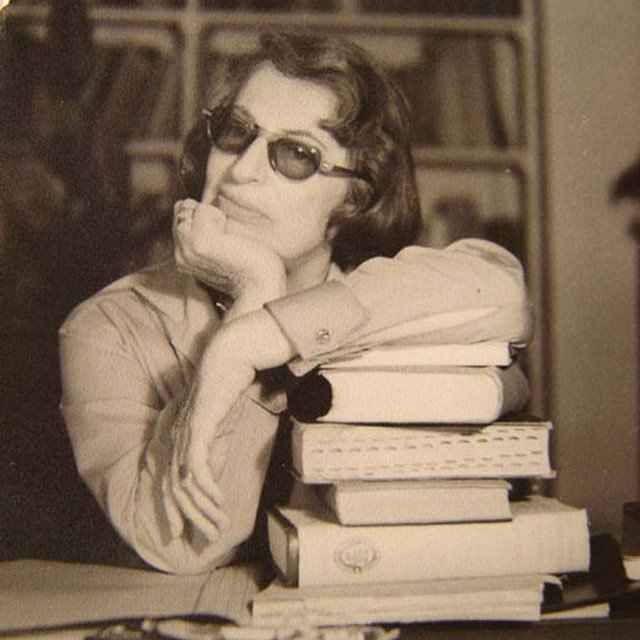

Silvina Ocampo (1903-1994) was an Argentine poet, short-fiction writer and translator whose works include Poemas de amor desesperado, Amarillo celeste, Autobiografia de Irene, and La furia.

Suzanne Jill Levine has written several studies of Latin American literature and is the author of Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman: His Life and Fictions.