Ɪ

THE CAPTAIN AMIANA! He’d been there for ten years. There were people in the world who had given him up for dead, people who had known him. Not the rest of us. We didn’t know anybody. Amiana used to keep a two-master over in Havana when he was busy hauling illegal immigrants to the United States. Poles, Syrians, Russians, Czecho-Slovaks, Germans, Armenians, Galicians, Portuguese, Jews. From all over. Amiana charged them for hundred dollars a head and then threw them overboard. Overboard, just like that. He knew the coast guard was out there somewhere watching, through gunscopes, and he couldn’t put them ashore. That happened sometimes. Then it was uncovered and Amiana had to take off. He unfurled his sails and disappeared. The papers said the coast guard had nabbed him and they published his picture. And meanwhile….

Ten years before, I mean. A crew went with him and they sailed leeward due west, and came upon the Island. There he folded his wings and never again was a bird’s cry heard on that island. The ship ran aground on the way in and he didn’t realize it was running on land until it beached in the mud, where some little branches, too green and too dry, were growing, spying like vermin, and farther on, the mangroves. The ship was stuck there to the hilt. Amiana gave orders to lower the topmasts and to cut a path inland to the bush. A path to nowhere. Everything was the same there, and there was nowhere to go. It was like cutting paths in the sea. The bush was low there, a little taller than Amiana, very thick and uniform. It wasn’t the jungle, with musical scales, with undulating terrain. It was the sea, a watery tortoise afloat on other water. To walk through that land men had to go by their inner compass, or by the stars. The men who weren’t sailors had to go out moored to a cable like divers, to be able to get back to the beached ship, their only guide. Which is why it all happened. Because the Island was not alive. It was an apparition, like the undead. One felt that beneath it something was fluttering that did not flutter, that did not have a dead life, that saw things through other eyes. The sea looked at the moon, and vice versa, and they did not see each other. The sea did not foam with whitecaps, nor did it have anything to say in itself, or to hear, and the moon was a bit of stunned sky, a rotting welt in the sky, as the island was a stunned welt in the sea. The island and the moon were two apparitions; the island was as mute as the moon, just as unreal.

But a sailor can sail on shore, too. Amiana put his people in the bush and there he opened a clearing, founded a city. This was the City, and that was all there was. It was a half mile from the sea, where I saw it, made up of the houses of the batey, a compound of wooden buildings seated on pontoons, like a lake village. The soil was soft and things were sinking, even the trees. Something was pulling from below. The house of the commander, Amiana, was higher, painted red, and those of his crew pressed in all around. A kilometer away were the barracks and the batey, where the slaves were. To the right and left, between barracks and batey, were the cemetaries, one for freemen and one for slaves. They looked alike from the outside. They were natural stockades of trees joined by crossbeams. Inside, no. The one for slaves was bare, except for grass. Amiana wasn’t concerned with this. He had other things on his mind.

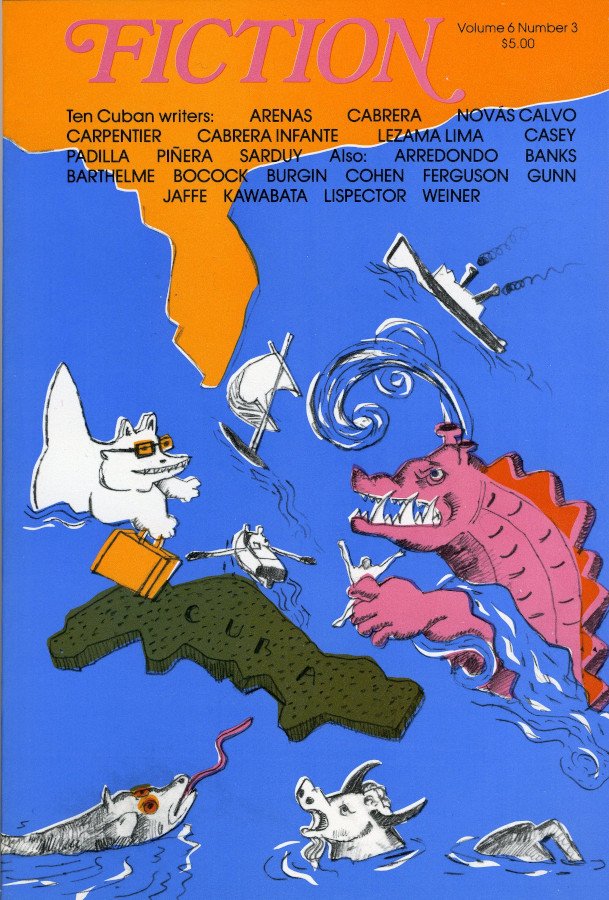

The full story can be found in Fiction Volume 6, Number 3. Please follow the subscribe link for information on ordering.

LINO NOVÁS CALVO was born in 1905 and later immigrated to Cuba. He was the first to translate Faulkner, Aldous Huxley, and D.H. Lawrence into Spanish. “The Night the Dead Rose from the Grave” was written in the forties. He has been living in the United States since the Revolution.