Masthead

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Mark Jay Mirsky

SENIOR EDITOR

Faith Sale

MANAGING EDITORS

Lyn Rintoul

Rebecca Stowe

COPY EDITORS

Roger Kasunic

Celine Keating

EDITORIAL ASSOCIATES

Gil Haroian-Guerin

Lisa Katz

Hava Morali

SPECIAL EDITOR: CUBAN ISSUE

Suzanne Jill Levine

CONSULTING EDITOR

Marianne Frisch

LAYOUT

Inger Johanne Grytting

Quotes from the Issue

“Its huge eyes brimming with evil, the Serpent seemed to offer the apple to the viewers of the painting.”

If you tweet out a picture #FictionVol6No2 and tag us @fictionmag, and we’ll feature your tweet right here on our website!

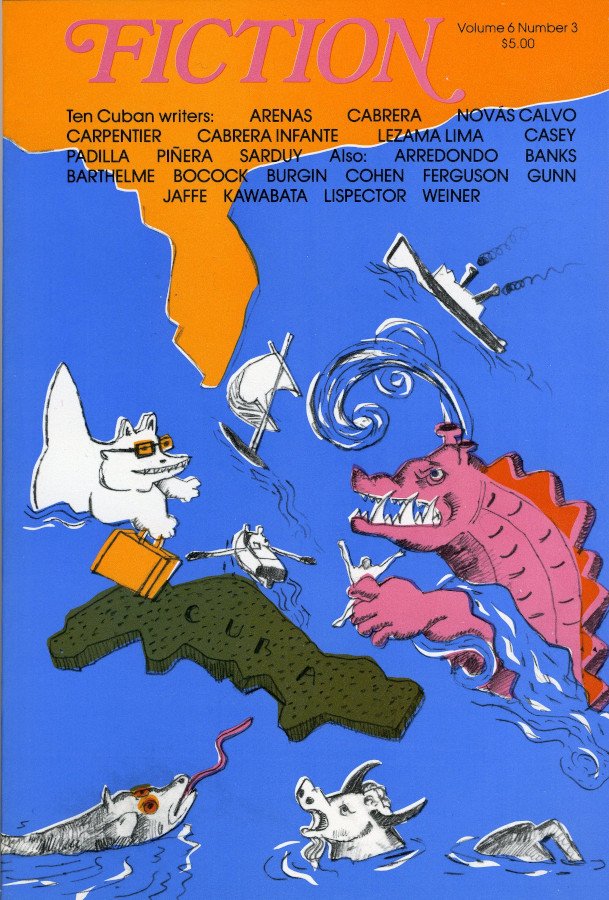

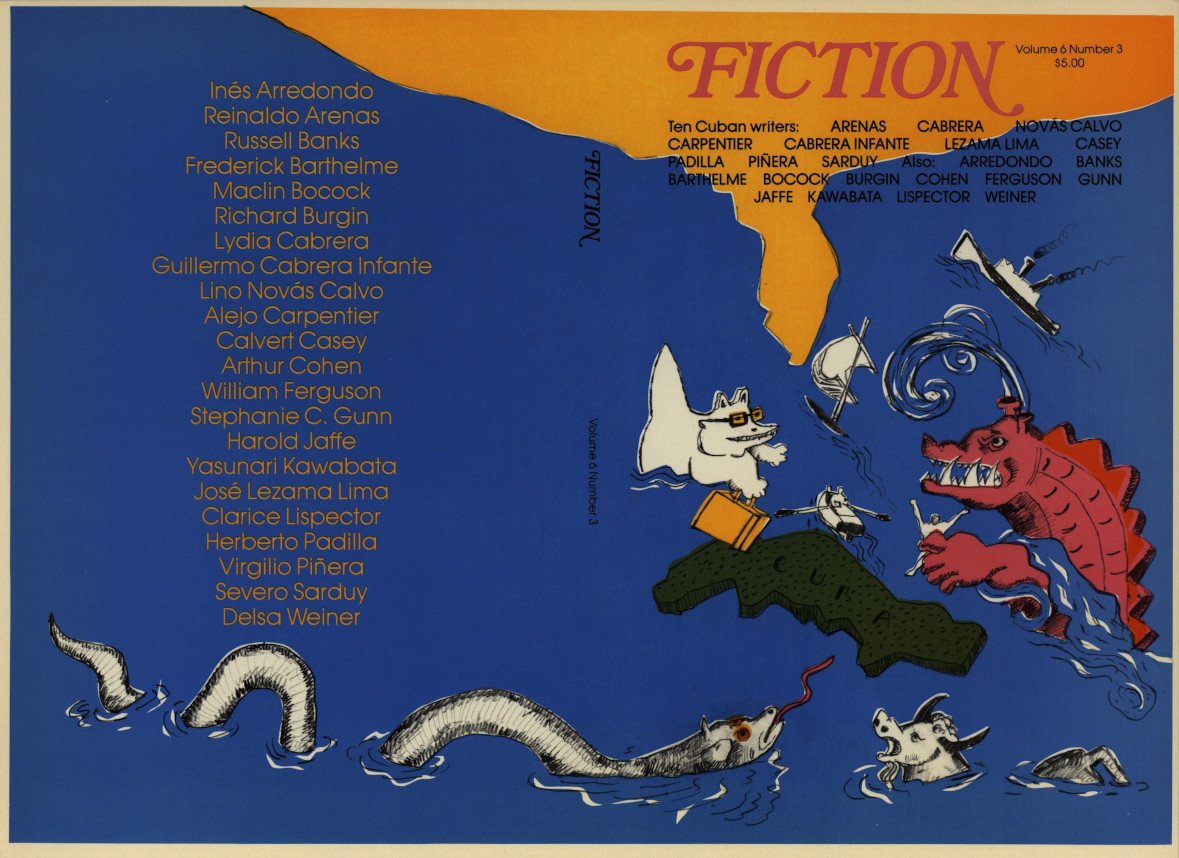

Volume 6 Number 3

Foreword

Ten writers have been chosen here to represent Cuban fiction from 1940 to 1980. The pieces selected, written before and after the triumph of the Revolution, in exile as well as on the island, offer an eclectic view of Cuba, in which national roots and political beliefs are transcended by an artistic vision.

Followers of Latin American literature in English may already be acquainted with Alejo Carpentier, José Lezama Lima, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and Severo Sarduy. Of Reindaldo Arenas only one novel, Hallucinations (Harper & Row, 1971), has been published in English. Virgilio Piñera (playwright and poet as well as fabulist), Lino Novás Calvo, Calvert Casey, and Lydia Cabrera are unfamiliar to most North American readers.

The raw material of Lydia Cabrera’s humorous Afro-Cubanesque inventions shares affinities with the basic legends and fables of many nations; it is curious that she, like Carpentier and the Guatemalan Miguel Angel Asturias, first considered seriously her Latin American roots while studying in Paris. She went to Paris in the twenties to study oriental art at the Louvre, the same school that Severo Sarduy would attend four decades later. Carpentier and Cabrera Infante, poets Lezama Lima and Sarduy, all seem committed more to a universe of metaphors than to an island of lush foliage and harsh socio-political realities. Virgilio Piñera, Reindaldo Arenas, and Calvert Casey appear more preoccupied with inner worlds than with the Revolution. And yet one can easily see how Cabrera Infante’s or Arena hermetic visions of Havana are as “true-to-life” as the naturalistic portrayal of a hallucinated island obsessively detailed by Novás Calvo (translator of Hemmingway and Faulkner). His grotesque account about an oppressor and his oppressed subjects reveals once again—like Lezama’s and Sarduy’s mysterious mazes, like Casey’s Roman heaven and hell, like Carpentier’s baroque (or rococo) deceits—that Cuba, indeed America, is a figment of some mad dreamer’s imagination.

As translation editor of this Cuban collection, I have revised or collaborated on the pieces included, with the exception of Calvert Casey’s story, written in his own brand of bilingual English, and of Anthony Kerrigan’s rendition of Herberto Padilla’s poem (in a magazine called Fiction, a future proof of our eclecticism!). I have also included two translations of my own, from works-in-progress.

Suzanne Jill Levine

• • • • •

Fiction’s attraction to Cuba was, I imagine, inevitable. Our magazine has a stubborn notion of tilting against the prevailing rush of the windmill—North America’s preoccupation with fantasy which does not depart from the procession of natural detail in life. Without a program for “surrealismo,” “ultraismo,” or “exhibitionismo,” Fiction through its regular pages, as well as in its special issues on contemporary German fiction and the River Plate writers, has tried to call attention to fantasists whose fiction reimagines the world. A comprehensive survey of Latin American fiction is far beyond the scope of the magazine, even a representative collection of the best in such a small geological locus as Cuba. Some of the names included here are better represented in their larger works: Carpentier is The Lost Steps; Lezama Lima in Paradiso. This was so for the River Plate writers as well. However, a clear difference in narrative energies, in tempo of imagination, and in rhythm is immediately apparent even in translation when opposing the rococo pace of the Cuban with its African melodies, the storm of the Havana dance floor, and ghoulish Caribbean nightmares to the reserve and decorum characteristic of the River Plate school. The differences are marked when contrasting the lurid joys of Severo Sarduy’s theater of horrors with the pathos of Juan Carlos Onetti’s characters shifting into dead-end dream worlds in sober despair. One can remark though that the literary playfulness and metaphysics of the Argentines, of Borges and Bioy Casares, are evident in most of the Cubans, insisting only that the beat is different. Cuban fiction has a syncopation which stirs the languid pot of “tropicalismo”—that dangerous wallowing in the baroque jungle which has trapped some of the major writers of South America in a swamp of their own making. Spicy, even excessive perhaps to the staid American palate, in their own peppery way the important Cuban writers remain true to the distinguishing characteristic of fiction as a form of art rather than entertainment. The fantasies, grim and fevered by turns, seek to draw the dimensions of a world where action is determined by hallucination and where hallucination is often the greater part of the day’s reality. Four novelists appealing to very different imaginations— Alejo Carpentier, José Lezama Lima, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Severo Sarduy—from this tiny island, in a space of twenty years or so, have gone to the outer limits of man’s space in ideas of time, order, and meaning.

At moments, I admit, without the poetry of the Spanish in my ear, I may have despaired of following them to the final bursting novas, but the star charts of their astrology remain fixed in my own thoughts of journeys as a novelist. Too often in the larger anthologies of Latin America the sense of place is lost, that feeling for connection by geography and the linguistic definition, turn of phrase, turn of mind. By bringing some of the Cubans together in Fiction, even in brief passages, we hope to give the reader an idea of their very special music and to provoke the critical to define what we believe is an intense galaxy in the brilliant mid-century moment of Spanish-American writing.

Mark Jay Mirsky

Contents

Alejo Carpentier

Lydia Cabrera

Lino Novás Calvo

Virgilio Piñera

Calvert Casey

Guillermo Cabrera Infante

Severo Sarduy

Reindaldo Arenas

Herberto Padilla

José Lezama Lima

Glen Baxter

Yasunari Kawabata

Richard Burgin

Maclin Bocock

Arthur Cohen

Harold Jaffe

Frederick Barthelme

William Ferguson

Inés Arredondo

Clarice Lispector

Delsa Weiner

Stephanie C. Gunn

Russell Banks

Baroque Concerto

The Women Were No Match for the Frogs

How the Monkey Lost the Fruit of his Labor

The Night the Dead Rose From the Grave

Hell

On Insomnia

The Journey

The Wedding

The Acteon Case

Piazza Margana

You Always Can Tell

The Instructor

In the Shade of the Almond Tree

Hard Times

Decapitation Games

Drawings

The Little Girl on the Tsubame

Some Notes Towards Ending Time

La Humanidad

Points of Origin: Where My Mind Comes From

The Artificial Son

Magic Castle

Space Invaders

Mariana

Pig Latin

Lester's Wife (1960-1978)

Bunny Says It's the Deathwatch

The Child Screams and Looks Back at You

Special Thanks

• Charles Dietrick and Suzanne Jill Levine translated Baroque Concerto from the Spanish.

• Mary Caldwell translated The Women Were No Match for the Frogs and How the Monkey Lost the Fruit of his Labor.

• Charles Dietrick translated The Night the Dead Rose From the Grave from the Spanish.

• David Pritchard translated Hell, On Insomnia, The Journey, The Wedding, and The Acteon Case from the Spanish.

• Suzanne Jill Levine translated You Always Can Tell and The Instructor from the Spanish.

• Andrew Bush translated In the Shade of the Almond Tree from the Spanish.

• Anthony Kerrigan translated Hard Times from the Spanish.

• Rachel Phillips Belash translated Decapitation Games from the Spanish.

• Ruth W. Adler translated The Little Girl on the Tsubame from the Japanese.

• Margarita Vargas and Bruce-Novoa translated Mariana from the Spanish.

• Alexis Levitin translated Pig Latin from the Portuguese.

Brief Excerpts from the Issue

Notes on the Contributors

REINALDO ARENAS, born in Cuba in 1943, left there during the 1980 exodus. He has written three novels of a projected five-novel cycle, Hallucinations (El mundo alucinante), which has been published in English, Celestino antes el alba (Celestino Before Dawn), and El palacio de las blanquísimas mofetas (The Palace of Pure White Skunks). He now lives in New York City.

INÉS ARREDONDO, born in 1928 in Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico, studied drama at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, and was a fellow at the Centro Mexicano de Escritores. She has taught at Indiana University and lived in Montevideo from 1963 to 1964. In 1965 she published La señal, of which “Mariana” is a selection. In 1979 she won the prestigious Villaurrutia Prize for fiction with her second book of short stories, Río subterráneo, published by Joaquín Mortiz. She now lives in Mexico.

RUSSELL BANKS’ novels include Hamilton Stark and The Book of Jamaica. “The Child Screams and Looks Back at You” is from Trailerpark, a book of fiction due from Houghton Mifflin in late 1981. Other sections of the book are forthcoming in Ploughshares, Mississippi Review, Sun & Moon, Shenandoah, and The Boston Globe Magazine.

FREDERICK BARTHELME teaches at the University of Southern Mississippi and is the editor of the Mississippi Review.

MACLIN BOCOCK lives in California. She has contributed to a number of quarterlies including Canto, Fiction International, and The Southern Review. This is her second appearance in Fiction.

RICHARD BURGIN is the author of Conversations With Jorge Luis Borges, a novel, The Man With the Missing Parts, and the forthcoming Conversations With Isaac Bashevis Singer. He is the founding editor of the New York Arts Journal and has published in many magazines and anthologies, including Partisan Review, Hudson Review, Chicago Review, Michigan Quarterly, Mississippi Review, Parabola, and The New York Times Magazine.

LYDIA CABRERA, born in Cuba in 1900, left there for Paris in the twenties. One of the first white writers to study the African roots of Cuban culture, she has published books on Afro-Cuban religion, costumes, and music, books of African names in use in Cuba, and two collections of Negro short stories. She has been living in the United States since the Revolution.

LINO NOVÁS CALVO was born in 1905 and later immigrated to Cuba. He was the first to translate Faulkner, Aldous Huxley, and D.H. Lawrence into Spanish. “The Night the Dead Rose from the Grave” was written in the forties. He has been living in the United States since the Revolution.

ALEJO CARPENTIER was born in Havana in 1904. He briefly studied architecture at the University of Havana, then left to become a journalist, a radio-station director, and a teacher of music and cultural history. He has written a history of Afro-Cuban music and several novels, including The Kingdom of This World, Explosion in a Cathedral, Concierto Barroco, and The Lost Steps, for which he received the Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger in 1956. Carpentier was the cultural Attaché at the Cuban Embassy in Paris until his death in 1980.

CALVERT CASEY, born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1923, of an American father and a Cuban mother, was educated in Cuba but lived in New York from 1946 to 1957, when he returned to Havana. During the first years of the Revolution he was an editor and published his short stories in the literary magazine Lunes de Revolución. Soon after this magazine was banned, he chose his second exile in Rome, where he wrote his final story, “Piazza Margana,” in English. He took his life soon after. His single volume of short stories, El regreso, was published in 1963.

ARTHUR COHEN’s most recent novel is Acts of Theft. Others include The Carpenter Years, A Hero in His Time, and In the Days of Simon Stern. He lives in New Yorker where he is a rare book dealer.

WILLIAM FERGUSON teaches Spanish literature at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. His work has appeared in the Massachusetts Review, the Boston Review, Canto, the Mississippi Review, and Calliope. Last year, with Nancy King, he founded the Metacom Press, a Worcester-based private press specializing in limited editions of modern American authors.

STEPHANIE CURTISS GUNN was born in Toronto. The recipient of an M.F.A. from Columbia in 1979 and a 1979-1980 grant from CAPS, she has been published in Columbia, a Magazine of Poetry and Prose, and The Penny Dreadful. She is presently at work on a novel, The Life Itself Is Too Strong.

GUILLERMO CABRERA INFANTE founded Lunes, the literary supplement to Revolución, which he edited until it was banned in 1961. He was then appointed cultural attaché to the Cuban Embassy in Brussels and promoted to chargé d’affaires, but in 1965, while visiting Cuba to attend his mother’s burial, he resigned from his diplomatic position. His collection of short stories, Así en la paz como en la guerra, has been translated into French, Italian, Polish, Czech, Russian, and Chinese. His novels translated into English include Three Trapped Tigers and View of Dawn in the Tropics. He now lives in London.

HAROLD JAFFE has recently compiled a volume of short fiction called Mourning Crazy Horse. He is co-director of the Fiction Collective.

YASUNARI KAWABATA is best known in the West for his novels Snow Country, Thousand Cranes, and Sound of the Mountain, and for his early short story The Izu Dancer. Kawabata began writing in the early 1920s while he was still a student at Tokyo Imperial University. Soon thereafter he became one of the chief proponents of a new school of Japanese writing, breaking away from the extremes of realism typical of Japanese literature and attempting to develop a new, impressionistic approach. He was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1958 and died in 1972.

SUZANNE JILL LEVINE’s translations include Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s Three Trapped Tigers and View of Dawn in the Tropics, Manuel Puig’s Betrayed by Rita Hayworth, Heartbreak Tango, and The Buenos Aires Affair, and Adolfo Bioy Casares’ A Plan for Escape and Asleep in the Sun. She is an assistant professor of romance languages at Tufts University.

JOSÉ LEZAMA LIMA was born in Cuba in 1912. He is the author of the novel Paradiso (1966) and is represented here by a story published in the sixties. Lima remained in Cuba after the Revolution and died there in 1980.

CLARICE LISPECTOR lived in Brazil until her death in 1978. She is the author of six novels and four short story collections, of which the novel Apple in the Dark (Knopf) and the collection Family Ties (University of Texas Press) have been translated into English.

HERBERTO PADILLA was born in Cuba in 1932. He spent the year 1948 in the United States teaching in Berlitz schools. He returned to Cuba in 1949 and later worked as a journalist in London and Moscow. His books of poetry include Sent Off the Fields (1972), El hombre junto al mar (1978), Por el momemto (1970), and La marca de la soga. A book of his poetry translated by Alastair Reid will be published in 1981 by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. Padilla left Cuba in 1980 and now lives in the New York City area.

VIRGILIO PIÑERA was born in Cuba in 1912. He lived many years in Argentina, where he published his first novel, La carne de René, and in 1956 a volume of brief fantasies, Cuentos fríos (Cold Stories). On his return to Cuba, Piñera published a second novel, Pequeñas maniobras, and staged several plays. His short stories have been translated into French and Italian. He died recently in Cuba.

SEVERO SARDUY was born in Cuba in 1937. He is the author of Cobra, and his novella From Cuba With a Song appeared in the collection Triple Cross published by Dutton in 1972. He now lives in Paris.

DELSA WEINER received a 1979 Fellowship for Fiction from the Artist’s Foundation of the Massachusetts Council on the Arts. Her short story “Rendezvous with Daddy” appeared in the March 1981 issue of McCall’s Working Mother.

by Alejo Carpentier

THE WARDER NUN peered out distrustfully through the grate, pleasure transforming her face when she saw the Red-Head’s countenance: “Oh! Heavenly surprise, Maestro!” The door hinges creaked and the five men entered the Ospedale della Pietà, in complete darkness, the distant sounds of Carnival echoing in its long corridors from time to time as if carried on a frolicking breeze. “Heavenly surprise!” repeated the nun as she lit the lamps along the large music hall which was both monastic and worldly with its marble objects, moldings, and garlands, its many chairs, curtains, and gilt trimmings, its carpets and paintings of biblical themes: it was something like a theater without a stage or a church of few altars, both showy and secretive. They made their way to the rear, where a dome was hollowed out of darkness, candles and lamps stretching the reflections of high organ pipes accompanied by the shorter pipes of the voix celeste. And Montezuma and Filomeno were asking each other why they had come to such a place instead of seeking out wine, women, and song just as two, five, ten, twenty bright figures began emerging from the shadows on the right and on the left, surrounding friar Antonio’s habit with their lively white cambric blouses, dressing gowns, pearl earrings, and lacy nightcaps. And others arrived and still more, sleepy and sluggish as they entered, but soon playful and merry, whirling about the night visitors, testing the weight of Montezuma’s necklaces…