by Marc Palmieri

From Fiction Number 64 (2019).

I’D KNOWN FOR weeks that my father had gotten transferred to Long Island. We’d be moving in the winter after Christmas, and I’d be leaving my sixth grade class right in the middle of the year, but I kept it top secret at school, even from my friends. I hadn’t even broken the news to my teacher, Ms. Waters. Whenever it felt like the right time came each day, I put it off and tried to not think about it.

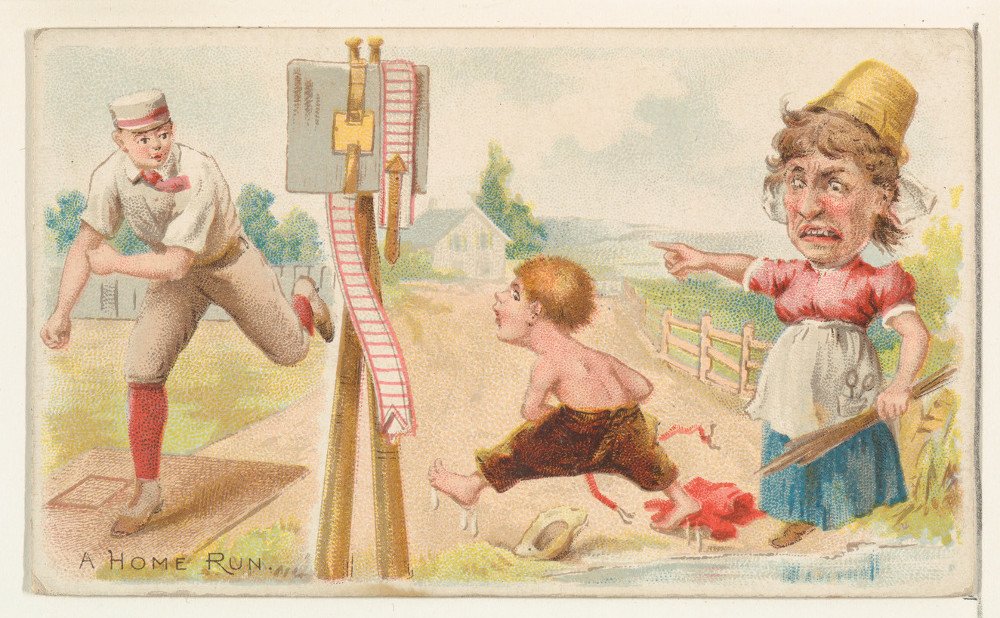

It rained most of October but at last it was bright and cool on a Sunday. There was a baseball game going on in Joe Lelly’s backyard. I was playing second base. We were in the third inning and all day, not once, did I think about moving, or feel the tight pain the thought of it caused in my stomach.

“Ma-arc!”

My mother’s voice came like a high, rolling moan over the rooftops and across Joe’s yard, like dark clouds of a cold front stealing your sunny day right in front of you.

“Ma-arc!”

It was my turn to bat again next inning.

“MARC!”

I knew why she was calling me.

“Isn’t that your mother?” Joe said from shortstop.

“Yeah.”

She called me two more times.

“Are you gonna answer?”

I walked as slow as possible. When I got home she was standing at the door.

“Dr. Lichten is here,” she said.

I found this bearded, bespectacled man sitting on our sofa with a glass of ice water in his hand. Dr. Lichten, it had been explained to me, was to administer an IQ test because the school district I was headed to had requested it. It was, my mother had explained, to help decide if I should be placed in the “gifted and talented” program.

I found him hard to look at. Until that moment moving had been an abstraction, a distant scenario, even a nightmare perhaps, which, no matter how many people visited to look around our house with the sales agent, seemed too cruel not to wake up from.

“Hello, Marc,” he said.

My mother walked us up to my room, where she sat us at my small desk by the window. Dr. Lichten removed from a briefcase a small pamphlet, pencils, a notebook and placed them on the desk. My mother left and returned a few minutes later with two glasses of water.

“How long will this take?” I asked my mother.

“Not long,” the man said.

My mother left and Dr. Lichten explained the rules. We’d go through each question in the pamphlet. He’d read the questions slow and loud to me, like I was an idiot, and I’d be allowed to take as much time as I wanted and use whatever paper I needed for scrap, until I chose an answer. All the questions were multiple choice.

“Ready?” he said.

“Yes.”

My window was closed but the day’s breezes and rattling leaves could still be heard, muffled but lovely, like fans applauding at a ballgame blocks away. While Dr. Lichten would read the questions I’d crane my neck slightly to glance at his watch, thinking of all I was missing and getting angry. I wondered what “IQ” stood for and came up with some ideas between giving my answers. “Inside Quiz,” was one. “Idiot Question Test,” was another. “I Quit Test.” Then I ran out of ideas.

“Are we almost done?” I said. It had been nearly an hour.

“Only a few questions left,” he said, not removing his eyes from the page. “Then we’re finished.”

The afternoon light that had poured into the room and onto my desk had begun to bend and wane slightly. Dr. Lichten seemed to be reading slower and slower. The questions got more complex and he’d trace diagrams and confusing shapes with his pencil, which made things seem to drag even longer. I pictured the stairs just outside my room, descending swiftly beneath my sneakers. I pictured landing at the bottom, kicking the screen door open and running out into the great day again.

“Now try to focus, Marc,” he said. “What makes the most sense here in this arrangement? Look at the diagram and find the pattern.”

He reread the question.

“Letter B,” I said.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes!”

We got to the last question. On one leg I stood beside him, keeping only half my ass on my chair.

“Alright, now look at this one,” he said.

I tilted my head as if to be reading along with him, but aimed my eyes past his wiry hair and out the window into the swaying trees. Outside it was easier for everything, especially to forget about Long Island.

“Letter C!”

“You sure?”

“Yep! Next!”

“Okay. Well, there’s no next. You’re all done,” he said, and stood up.

We came down the stairs. My mother met us in the living room.

“So how’d we do?” she said, rubbing her palms together.

“Mom, can I go back to Joe’s?”

“In a second,” she said. “Is that all, Doctor?”

“That’s all,” he said. “You want to talk about it?”

My mother turned toward me.

“You want to know how you did, Marc?” she said.

“Tell me later.”

“You did fine,” said the doctor, then he turned to my mother. “It’s a very simple scale.”

He pulled out a sheet from his bag and held it out at my mother.

“Okay,” she said. I stood there and tried to see it.

“Now Marc places about here.”

He held his pencil tip to the sheet and made a circular motion with it. My mother’s small smile vanished completely for a moment, before something else took its place.

“Okay,” she said again, differently.

“Can I see?” I said.

He took the sheet from my mother and held it up for both of us to see at once. There was a line horizontally across the page and a small, light oval from his pencil on an area in the middle, just near the word Average. On the extreme right of the line, far from the oval, was the word Genius.

“This is where most people finish,” he said, pointing to his mark at Average with his pencil. I set my eyes on it, then over again at Genius.

“You finished right here, Marc,” he said.

My mother smiled then. A little.

“Just like most people,” she said.

I arrived at Joe’s backyard after the game was over. Most of the other kids had gone home, but a few remained lying on the grass, faces turned upward at the sky. I approached and stood over Joe.

“Lie down,” he said. “It’s all dry now. The sun and wind dried it all fast.”

I lay on my back beside him. A few shallow clouds moved fast across the sky, while some further back seemed heavier and still. The contrast was strange to me, and beautiful, until I thought how I had never noticed such a thing in the sky before. I thought that I must often miss things like this, genius things. Even if they happen right in front of me, I thought, there would be many things I’d never notice, or understand. Just like most people.

“Where were you all day?” Joe said.

“I had an IQ test.”

“How was it?”

“It was fine,” I said. “Boring. Easy.”

We were quiet awhile. I tried not to, but again I thought of Ms. Waters, and of seeing her in the morning. I thought of approaching her desk and telling her I was moving. I hadn’t told anyone, but tomorrow would be the day, I decided. I was sure of it. I’d make it official. I’d tell her in the morning. First thing. I was leaving forever.

My stomach was killing me.

“So what do you want to do now?” Joe said.

“Nothing with you,” I said.

“What?”

“You heard me.”

Joe sat up.

“What’s the matter with you?” he said.

“We can’t be friends anymore, Joe. I’m sorry.”

“Why?”

I stared at the sky.

“Why?” he said again.

“Because I’m a genius.”

“So?” There was panic in his voice. “So what?”

I sighed. I felt lightheaded.

“So I have to concentrate, and be around smart people, you dumb bastard.”

A good feeling came over me. Then I told Joe I was moving far away. I told him that I’d be in the gifted and talented program when I got there, and that I couldn’t wait. He got more and more upset, and kept asking why, but that was all I gave him.

Joe went home crying. My stomach felt better for a while, until the next day, when Ms. Waters’ smiled and said she had no doubt that I would do great on Long Island, and make lots of friends, and be happy no matter what.

“You’ll see. I know it, Marc,” she said. “I do.”

Ms. Waters was beautiful and kind, and always smiled at me. Always. I loved her, I think, even then, as she was lying to me, and didn’t know a damn thing.

by Sonja Killebrew and Afsana Ahmed

Marc Palmieri is a professor, a writer, an actor, and even a baseball coach having once played for the Toronto Blue Jays. His plays, such as Waiting for the Host, Poor Fellas, and NY Times’ “Critic’s Pick” Levittown have been performed not only in New York City but around the country. His script for Telling You was produced by Miramax and stars Jennifer Love Hewitt.