Fiction, headed by editor-in-chief Mark J. Mirsky, is a literary publication that was established in 1972. Since its inception, Fiction has aimed to bring the experimental to a broader audience, and to bring new voices to the forefront, publishing emerging authors alongside well known and established writers.

Masthead

Editor Mark Jay Mirsky

European Editor Marianne Frisch

Consulting Editors Jennifer Lyons, Ruth S. Mirsky

Managing Editor Sonja Killebrew

Assistant Editors Afsana Ahmed, Milena Blue Spruce

Associate Editors G.D. Peters, Lissa Weinstein

Art Consultant Inger Johanne Grytting

Web and Online Editors Chris Bonfiglio, Ruth S. Mirsky

Social Media Manager Pin I Wu

Copy Editors Milena Blue Spruce, Jo McKendry, Ruth S. Mirsky

Editorial Associates Domenick Acocella, David Braslow, Francette Carson, Jenniea Carter, Denise Domena, Jack Eisenthal, Leah Elimeliah, Taco Hossain, Kayla Greene, Sara Jacobson, Harry Lai, Wendy Meza, Kaz Sutherland, Nathaniel Wachtel

Design and Layout Debbie Berne

Telephone 212-650-6319

Email fictionmageditors@gmail.com

Twitter twitter.com/fictionmag

Instagram instagram.com/fiction.magazine

Facebook facebook.com/fiction.mag

About the Magazine

How and why did the magazine Fiction begin? The following is from a long autobiographical piece on Donald Barthelme that remains unpublished, though it draws in part from an account I did publish when he was still alive. Without Donald Barthelme there would have been no Fiction. He was for its first critical year, the puppet master, though at times I didn’t appreciate just how deft his fingers were on the strings. I told a part of the story years ago in TriQuarterly at that magazine’s request.

Donald was looking over my shoulder. I was therefore circumspect, but reading it over, the pages still ring of the moment. "I started Fiction out of desperation. One is supposed to be ashamed to admit such things. A friend, wife of a prominent New York publisher, recently accused me of being generous and ruthless by turns. But I’ve never seen myself as the latter—just desperate, a state which comfortable, lucky people often misunderstand.

Fiction was begun at a time when fewer and fewer magazines were taking stories for their pages, to say nothing of excerpting novels. . . . In 1970 and 1971, however, friends like Stanley Elkin and John Hawkes couldn’t get their best fiction printed in periodicals. . . . I railed against a whole kingdom of periodicals—Esquire, New American Review, the Atlantic, bewailed the realm of dead issue, Harper’s Bazaar’s discontinued fiction section, the defunct Saturday Evening Post. I cried out under a banner, and that banner was Fiction.

Several incidents provoked this flag waving. Stanley Elkin came to New York to read at City College. He recited a section of The Dick Gibson Show so funny that students were falling down in the hall, banging hands on the floor, against the walls, to try to stop laughing. I asked Stanley’s friend, Gordon Lish, why Esquire didn’t run the pages—a tall tale about a lady with an oversized private part, shopping under the eye of a lunatic pharmacist. Lish told Elkin to change the erotic key to the chapter and maybe he would consider it. No doubt Lish was under the yoke of Esquire’s puritan hangover, but it was an editorial attitude that put the book of Hosea beyond the pale of decency. Esquire, however, was a lamp unto my feet compared with Playboy or Penthouse, where one could be sure of reading a famous writer’s worst fiction. . . . Worst of all was reading the regional reviews from around the country . . . the hack stuff they represented as the experimental short story.

It was a bleak moment in which we were born, which probably explains some of our noisemaking: the fact that for an instant we were able to get national attention—the back page of the New York Times Book Review, New York Magazine’s "Best Bets," a lot of newspaper coverage around the country. For a brief space it looked like a miracle. Let us pause at that second, enjoy its glow. I slyly hope that the attention we got did change, at least in the quarterlies and reviews.

I pause here. Partisan Review’s fiction is dismal. Paris Review’s is checkered. There is more interest in fiction now, however, and the glow of Tom Wolfe’s Brave New World in which fiction would largely disappear, replaced by New Journalism is fading. Mailer has rewritten the Gospels—that is a sea change. It is Donald though, I am interested in, and he appears in the next paragraph of the TriQuarterly piece.

Now I am forced to take the lamp from under my feet and shed the limelight on the features of one who habitually professes to detest it. Fiction owed its existence to Donald Barthelme. He kept ragging me when I came over to talk with him. "When are you bringing out that magazine? I’ll do the layout for you." I had been trekking over to Donald’s to listen to his talk about books and show him my own work. At one moment I had angrily threatened to bring out a magazine in pure spite at the vast conspiracy of indifference. He took me up on this vaunt during a late afternoon hour when I was well pickled in a friendly glass of Scotch. "When are you bringing it out?" he asked afterward, whenever I saw him, again adding the fateful words, "I will do the layout."

I used to meet Anne Waldman on street corners as I walked past Saint Mark’s Church in the Bouerie, where we had both once worked in the theater. She and I would discuss Angel Hair, her mimeograph magazine The World, and the costs of printing, cheap and expensive. In the back of my mind was a conversation I had had years before with Rudy Wurlitzer over coffee in a dingy East Side luncheonette on Avenue B about the possibility of bringing novels out in newspaper format. Offset printing had briefly revolutionized publishing by cutting the costs of typesetting drastically. If one embraced the newspaper format, which was cheap to print, perhaps one could reach an enormous readership by distributing literature for pennies. Dreams of an underground audience of good readers began to haunt me. O vain illusion.

At this very instant, into my office at the City College English department walked a fireball named Jane DeLynn. Jane was looking for a teaching job. There was nothing, but as her legs and her tongue flashed I was moved by inspiration: ‘Why don’t you become my managing editor?’ I was outlining the hypothetical magazine as she snapped, ‘Absolutely.’ And we were off and running.

While Jane DeLynn hunted out the cheapest of printers, Donald Barthelme produced for us a handsome dummy page which was the basis for the first issue’s design and layout. In the next few months, before we saw that issue, whenever my energy lagged I would look at the three elegant walls of type on the page, the collage which floated within them. I knew that if we never went beyond a single number of Fiction, it would be worth it, whatever the contents, just to hold the work of Donald’s eye in my hands.

I had to hug the dummy many times. City College kept blowing hot and cold on the project. I felt that the financial support of the college was critical if we were to be able to open an office, send and get mail, answer telephones. I was blissfully ignorant of how much time Fiction would be stealing from my writing and teaching. In an English department committee meeting I had received a pledge from the powers-that-be to underwrite the magazine. But when I had the dummy in hand—stories in manuscript from Stanley Elkin, Donald Barthelme, John Hawkes, Max Frisch, Jerome Charyn, etc.—I was suddenly told that the funds were not there. I knew I couldn’t wait. I swore silently. I collected pledges of financial support from friends. And when the issue went out to the typesetter, I went to the bank and withdrew the money from my savings account. Page after page appeared mysteriously before us—before me, a neophyte, as Donald bent expertly over the shoulder of the young man at the layout table. I trembled, holding the check from the bank in hand. Alas, we celebrated boisterously the paste-up of the final page—prematurely, it turned out, as someone spilled a glass of Scotch over them and it was a number of hours or a day or so (a happy alcoholic haze here obscures the details) until they were done.

Of course, the "someone" was Donald. He had gone up to the typesetters to supervise the final paste-up. He brought his bottle with him. It was one of those rare moments when I saw him in boyish embarrassment. The charge incurred to redo the ruined "boards" was trivial compared to the intimacy gained in that moment of seeing him holding the wet paste-up, abashed. Donald together with two friends of mine had chipped in to help reimburse me for our first printing. He was also instrumental in securing our first grant from his friend, Thomas Hess’s foundation.

Now, before the pandemonium starts, I have to mention a few more people. Donald Barthelme pulled me aside as we were assembling the issue at his apartment and said, "There’s a woman downstairs who is willing to help you with the copy editing." It was Faith Sale, who quickly became a valuable member of the editorial board, joined by my close friend Jerome Charyn [who consented when he saw the success of the first, to join us for the second issue].

Here again, I have to interrupt. Faith and I were set up by Donald almost from the very first. She had been an editor before and was reading, I believe, for Book of the Month Club. Many of our most important submissions came through her. She was far shrewder than I when it came to understanding commercial fiction but not as sympathetic to surrealism, or the experimental novel. (There were some exceptions on her part, Donald’s work, Ron Sukenick’s: she and her husband, Kirk, were close friends of Thomas Pynchon, whom I met once in her basement apartment.) Donald enjoyed arbitrating between us. Faith, moreover, put so much hard, free work into copy reading the magazine that she was more than alert to my tendency to irresponsibility, my desertions of duty at the helm (I was often on the motorcycle escaping into the country when she was toiling over proofs) and not shy about scolding me. This was just what Donald loved, two editors at daggers with each other—he as the pacifying father. Faith’s voice when she got angry so resembled my mother’s that I could feel the boils rise on my neck. He must have known from the very first we would be antagonists, and it was only late in the game that both of us understood what was going on and called a truce.

Faith has just passed away and so I am inclined to piety. Donald appreciated her, helped her back onto an editorial ladder that brought to Dutton, then Putnam (where she brought him from Farrar Straus), promoted her at P.E.N., but I sensed that she often felt undervalued. The role she fell into with Donald was compounded of motherly concern and the jealousy of a sister treated like a poor relation. At times, West 11th Street, Faith and Kirk Sale and their children in the basement, just below Donald’s apartment on the first floor—aware through their windows or the buzzing of the door bell every time someone visited him—Grace Paley just across the street—resembled a 1960’s commune. Though a very sad one when the game of musical doors was played. Donald divorced and Birgit, his Danish wife, and Anna, their daughter, revolved to his bachelor apartment down the street.

Finally, the presence at this precise moment in New York of the Swiss dramatist and novelist, and his wife Marianne (who was translating American writers into German), their enthusiasm for Fiction, their willingness to share their contacts with us, made a large difference. The Frisches created something unique in that city for a few months—a European salon at which writers met each other, talked, quarreled, were introduced, scolded. One came in from the cold, lonely plain of America to a warm literary parlor. It was impossible in such an atmosphere not to talk about a second and third issue of Fiction, if only to bring the new names one was hearing about, discussing, together under the magazine’s roof.

The efforts of all the editors, named above, and those of a publicist, Kathy Hartmann, who gave us her time and effort gratis, produced a sudden thunderclap of publicity. At one point, not only did we get attention from the newspapers already mentioned, and others—the Washington Post, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, etc., but the Today Show called. If we could produce one of our famous writers, they would be interested in having us on television. [I asked Donald, whom they were angling for, but he refused.] In a 'Guest Word' editorial in the New York Times Book Review, Fiction had asserted:

We simply cannot believe that people have tired of stories, that the ear of America has atrophied permanently and is now deaf to myth, fable, puzzle, paradox. . . . Literature is a mirror image of our own complexity—a necessity not a luxury. That is why we have spent a not inconsiderable amount of time and labor, plus a little money, in an effort to find new audiences. The 5,000 copies of our first printing melted away. Ten thousand more are just off the press and frankly we were amazed at the demand, stores like the Gotham Book Mart going through 250 copies in a few weeks. As we gather material for our second issue, we dream of reaching higher and lower, to the streetcorner, to the benches of power, as Charles Dickens did with his cheap pamphlets. Illiterate workmen used to hire readers to recite Dickens to them as the chapters appeared. Can we live without fable? What a dreadful impoverishment.

. . . Writers must take matters into their own hands and search out the audience they believe is there. Gather the singular, the quixotic, the recondite, try even with the clamor of the bazaar around them to tell a curious tale. By going outside the marketplace (none of us at Fiction, writers, artists or editors, have been paid) without grants or foundations, we have begun. As the Chairman says, seize the day.

Brave words. Aye. For a moment the novelty of what we were doing, the newspaper format, the illusion that adult fable was as easy to read as a child’s fairy tale, the newspaper, media attention, and some intangible historical freak did make those copies melt away. Most of them were never paid for, but that’s another story-the wars of the newsstand deliverers, the piracy of distributors, the Mafia, etc. . . . Half a year later, Tom Wolfe attacked us in Esquire:

The idea that the novel has spiritual function of providing a mythic consciousness for the people is as popular within the literary community today as the same idea was with regard to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England. . . . Mark J. Mirsky writes a manifesto for a new periodical called Fiction devoted to reviving the art in the 1970’s and he says . . . quoting Thoreau, ‘In the mythos a superhuman intelligence uses the unconscious thoughts of men as its hieroglyphics to address men unborn.'

Nothing could be further from the minds of the realists who established the novel as the reigning genre over a hundred years ago. As a matter of fact, they were turning their backs, with a kind of mucker’s euphoria, on the idea of myth and fable, which had been the revered tradition of classical verse and French and Italian style court literature. It is hard to realize today just how drenched in realism the novel was at the outset—realism pour le realisme!—all this is true of life! Defoe presents Robinson Crusoe as the actual memoir of a shipwrecked sailor. . . .

Esquire refused to give me space to reply. . . . Wasn’t Tom Jones a parody of Oedipus Rex, the old myth of the hero who sleeps with his mother? . . . As for Robinson Crusoe, what really sold the book then and now, was its magic, the fable of man returning to Eden. . . . Wolfe neatly had amnesia about the fantastic voyages in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Wolfe neatly had amnesia about the fantastic voyages in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, about Brontë’s Wuthering Heights," Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield. What I treasure in Dickens is the bizarre, the morbid, the grotesque, the fabulous and the intricate fairy tale of his plots. But in most of the nineteenth-century masters there is room for realists and surrealists to plead their case.

That guest word—the invitation to write it came from the Times through Donald. In fact Donald should have written it, but he didn’t want to be that closely associated—layout was sufficient as a title. (Little did I know how powerful that position was—but we will come to that.) So I was delegated to write the "Guest Word," a lofty honor but not entirely trusted to do so. Faith went over my first draft. I had never experienced a rigorous copyreader weighing my prose word by word and went a bit crazy. Then Donald stepped in—he didn’t change as much as I imagined—it was more an editorial process. I remember though, him holding up the draft and pronouncing, "Now, it’s time for a joke."

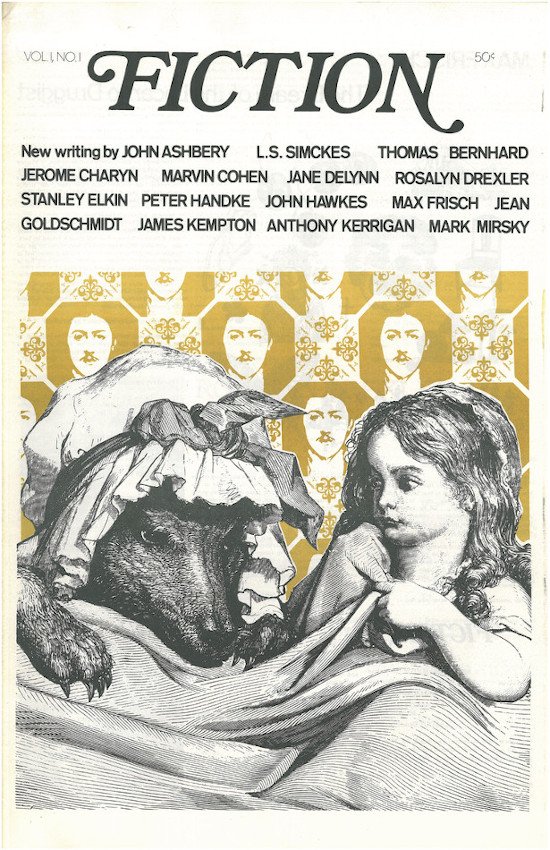

Donald’s whimsical but exacting sense of prose set us on our course, his allegiance was to the priority of language, not in any simple way. He was alive to metaphor, to the surprises of plot and to the surreal. In the autobiographical piece I wrote on him I detail some of the whacky moments we had when he served on the editorial board. In speaking here of Fiction, however, I would point out some of those treasures that lie hidden in the back pages of the magazine. Though they are collector’s items, the first two issues of Fiction like the third, show his extraordinary gift for layout. The joke of that cover, Marcel Proust’s face in the wallpaper behind Little Red Riding Hood (though the latter image has been staled through too frequent reproduction) still makes me smile. The first issue has an uncollected story of Donald’s—one that holds a bitter secret for those who are intimate with the details of his life.

Jerome Charyn came over last night and we were talking about Donald. I recently offered a long memoir I wrote about him to The American Scholar, and the editor wrote back that Donald wasn’t well known enough to justify an article there. To Jerry and me this seemed outrageous as we both regard Donald as one of the greatest stylists of American prose from the 1960’s through the 1980’s of the past century. He was a master of language and I often recall his remarks and repeat them to my writing students. As long as he was alive, both I, and my wife, who took over the layout from him, felt Donald staring over our shoulder and at each metamorphosis of the magazine, from its newspaper format, to its piano score size, to its final conventional dimensions, nine by eleven , he was consulted. His advice dictated the choice of type, and the subtleties of the layout. Donald had been a curator at the museum in Houston, Texas, and joined Harold Rosenberg and others on the magazine, Locations. You can see his playful sense of the art world in stories like "A Visit to the Tolstoy Museum." I’ll talk more about this world and illustrate some of it in my "History of Covers" on this Web site, but I want also to briefly allude to Donald’s talents as an editor. His cutting of Gunter Grass’s Diary of a Snail, a book that for all its talent was wildly overwritten, still makes me draw my breath in awe. Donald compressed Grass’s narrative into a poignant tense work of art. Alas there are no Nobel prizes for this skill and even when Donald’s genius was recognized, it was through the back door. He received a National Book Award (in part through the efforts of Lore Segal) for a Children’s Book. What a sad commentary on American Literary prizes!