by Heather E. Goodman

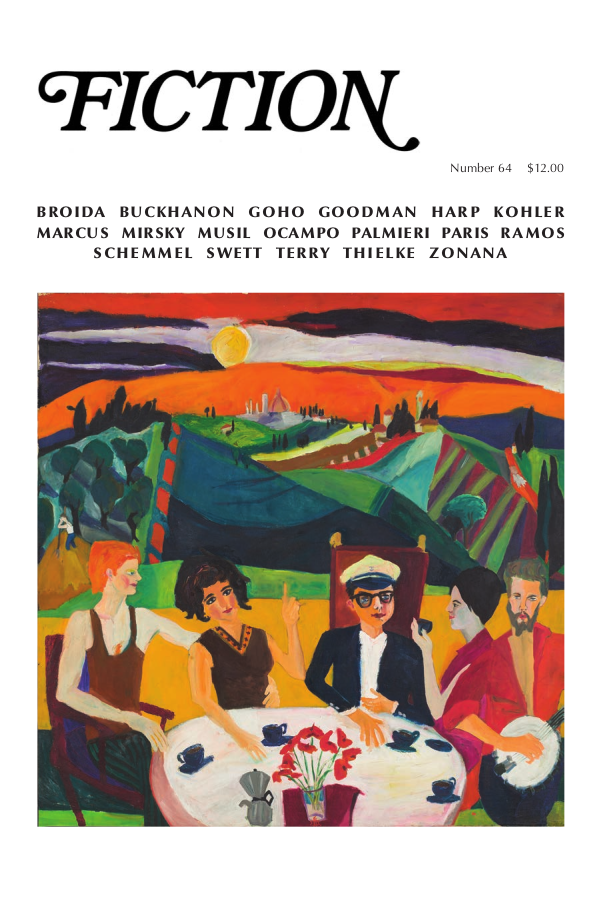

From Fiction Number 64 (2019).

LAUREL RACED FROM the woods, thinking Boone might have doubled back to the house after he bolted. It was hot, too muggy for early June, and she was out of breath after hustling up from the creek that bordered their seven acres. She yelled for Sam, who still called for Boone in the woods behind her. A truck in the driveway: engine wheezing quiet. She saw the shotgun. Stopped. Her voice in her throat, she listened. She could hear Sam’s feet in the leaves, maybe 150 yards off.

John Pick set his shotgun over his shoulder and let Boone out of the truck’s bed. Boone shook off, saw her and darted to her, tail wagging, tongue lolling. Laurel kneeled to him, wanting to be angry, but his dark eyes blazed wide and joyous.

Laurel called, “Oh thank you. We were so worried. There was a fox, and he—”

“Your dog killed my dog.”

Laurel stood from her bend. Her mouth filled with saliva, and she felt the sour spill at the back of her jaw. John Pick’s cap was slightly crooked, and his legs below his shorts were winter white. The backs of his running shoes were broken down, worn like slippers.

She lined up John Pick’s words. He rented one of the two farmhouses behind their woods and had woken them at 6:00 a.m. the morning after they’d driven in from Minneapolis eighteen months ago, saying the former owner was supposed to have left him a boat. They knew nothing about it, and after some polite chatter about the weather and neighbors, he’d left. Since then, they’d waved to him when they saw him driving down their unlined country road, often with his little black dog in his lap.

John Pick stared at her, his shotgun as casual as a scarf on his shoulder. Laurel was keenly aware she didn’t have a bra on and that Sam’s steps were still too far away in the woods. She asked, “Are you sure?”

“Head’s about tore off. You need to put your dog down or I will.

She inspected Boone, sitting at her feet, tongue long, bulky chest and head covered in drying saliva that spiked his fur. His ears were back, and he reached a paw towards her. Her gut smoldered. She examined Boone’s face, his mouth: no blood. But there hadn’t been the other two times either, not that he’d killed those dogs, but he’d sure as hell tried.

She heard Sam behind her and turned. “Bud!” he said when he saw Boone, and Boone trotted to him.

She watched Sam’s moss-colored eyes see the truck, see John Pick, see the shotgun.

John Pick called to Sam, “Your dog killed my dog.

Sam kept walking and Laurel wondered how.

Laurel watched as Sam looked at the dog, Boone nudging his hand.

Now she moved, she and he and Boone three rays coming to stand at John Pick’s truck.

Sam said, “He killed your dog.

“He’s here on the front seat.”

Laurel stopped. She couldn’t see another ruined dog, this one dead.

Time paused and pinprick focused, Sam shoved his hands in his pockets, bent to the truck’s window, backed up, stuttered. “Oh.” John Pick said, “Grabbed him and shook him like a rag doll. Wouldn’t let go. I would have shot him already, but by the time I got my gun, he’d dropped Tucker.” John Pick stopped speaking. Laurel saw his nose color, his eyes squeeze.

She took a breath. Hadn’t they known this day was coming? Hadn’t they moved to Pennsylvania, in part, to avoid it? Getting out of the city, into the country, going back to Sam’s roots, giving Boone space he needed, an electric fence instead of the physical fence he jumped to attack the second dog?

John Pick said, “Dog’s dangerous. put him down or I will.”

Sam dropped his head and that’s when Laurel’s eyes filled. Sam always had an answer, solved any problem: installed the new hot water heater, fixed wiring in the kitchen, recycled the former owner’s scrap heap in the yard. Got the job that allowed them to move. Married her six years ago after she’d been damaged goods. But even Sam couldn’t stop Boone.

Sam said low and throaty, “We’ll take care of it.

John Pick matched Sam’s voice and said, “There’s little kids around here. My nephews come to visit. I need to know you’ve done it.”

Sam nodded and Laurel looked at Boone, eyes wide, still puffing his big smile. The big oaf who rolled onto his back for the girl next door in Minneapolis, who cowered in front of tall men other than Sam, who low-crawled up the bed in between Laurel and Sam until all three of them shared one pillow. He had never hurt a child, never a person.

Sam hadn’t answered, so she had to try. “Mr. Pick—” she started, and he turned to her. “He’s such a good dog and—”

“He killed my dog.”

Laurel swallowed, shunned.

Sam said, “Can I have the vet send you a note?”

“Have his office call me.” John Pick ducked in his truck and pulled out a card, thumbing it to Sam. “By Monday.”

That night the deadline haunted Laurel. Boone had run off at ten. They had him back before eleven. By noon they’d come inside, Sam pouring tequila shots, then calling the vet’s office though they weren’t sure anyone would be there on a Saturday. Sam talked to Josie, the receptionist, explained the situation, and through Sam’s cell, Laurel could hear her response. “Oh, honey. I’m so sorry. We’ll get you in first thing. Could bring him now if it’s better?”

Sam had shaken his head, then choked, “No.”

Laurel could see Josie—pen behind her ear, cartoon animals on her scrubs—the office full of dog-lovers who never once demonized Laurel for owning a dog that needed a muzzle to walk through the office but then huddled in the corner of the sterile room, shuddering, muzzle off, licking the tech and Dr. Josh.

Sam worked out the details and said, “Thank you.” Boone lay on the floor, his broad chest heaving. They had forty-four hours left. The only family they’d ever been. After the first attack, she’d decided if she couldn’t raise a dog that didn’t maim, she sure as hell wouldn’t risk having children—Sam not sure kids were all they were cracked up to be anyway. Her own family’s Wednesday and Sunday dinners claustrophobic: unwanted financial advice, demands for grandchildren, and reminders of sacrifices made, all part of the push to leave Minnesota.

“Our adventure,” Sam had called it.

“Moving for love,” she had rallied back.

They did another shot and lay on the floor with Boone, who thumped his tail, then went back to his heavy breathing. Sam lay at Boone’s head and made him groan when he knuckled the inside of Boone’s ear.

Laurel smelled Boone’s popcorn feet and scratched his freckled belly. A breeze came in through the screen door and blew her hair. She looked outside beyond the patchy grass to the woods edge where she and Sam had burned the roots of Japanese barberry, an invasive the deer wouldn’t eat and a haven for deer ticks. They’d spent entire weekends burning and ripping garlic mustard, tree of heaven, exotic honeysuckle—so much destruction in preservation

When they’d finished, they toasted beers, their pride something to swallow if anyone else was around, but just the two of them, they could revel in it. They’d done the same after picking up all of the shotgun shells, cleaning up trash and tires along the creek, laying the wire for Boone’s fence, making the land theirs—restoring it, making it safe.

They’d caught trout and chubs and hunted turkey. Her gardens were heavy with lettuce and beans, coming-on tomatoes, cucumbers. Sam would hunt deer again in the fall. They ate off the land, filled themselves from this place they were healing.

Sam made venison burgers for dinner, giving Boone marbles of raw meat, and while the grill spit, he showed Laurel two mayflies on the window screens. She’d fallen in love with the sulphurs and duns, finer than dragonflies but with their same mystique. The hemlocks too, fine-feathered, similar to her tamaracks but green all year round. She hadn’t known Sam missed Pennsylvania so much until the move, their home an hour north of where he’d grown up. He showed her birds’ nests, seed pods, owl pellets, a new language, a new love.

They ate with their plates in their laps on the deck. Boone gobbled his burger in three bites. Sam shook his head, and the dog cocked his head at Laurel, sniffing towards her plate.

Sam asked, “Do you still want to go to the picnic tomorrow?”

“No.”

“I’ll text Jim.”

Sam had been looking forward to the picnic, a coworker and his wife hosting a party for old friends, but Sam and a couple others from the fledgling software company had been invited. Most of the people Sam knew from childhood had moved away or were involved in their young families, but he was starting to make new friends.

After the first attack in Minnesota when Boone was eight—a Yorkie that needed a dozen internal stitches and three times that externally, a bill that cost them a huge chunk of their savings—Laurel rationalized that she had a responsibility to Boone. Ten years ago, two years before she’d met Sam, she had adopted Boone from the Labrador Rescue Agency, though she and Sam joked only one ear was Lab, the rest a mystery, a muddy mutt if ever there was one. At the time, she had needed something to care for, so ruined by Adrian, her boyfriend, but still unable to free herself of him. Boone, a soft, dopey puppy, slept with his tongue out, ate her pens, and tackled blowing leaves. He’d been a sweet pup, without violence other than the pens.

After dinner, Sam and Laurel watched the sunset, and Boone barked and stormed the wood’s edge but didn’t break the line. They went to bed early, Boone trying to sleep in a ball at her feet. Laurel pulled on his forelegs, forcing him up to them, rubbing his head with two hands, asking, “What do you want to do tomorrow, Bud?”

Sam said there was a butcher’s bone in the freezer. He added, “We’ll all have venison steaks tomorrow night.” Laurel bit her lip; Sam rolled towards her, Boone smashed between them until he weaseled out and lay at her feet.

Laurel woke at 1:00 a.m., surprised she’d fallen asleep. She listened to the peepers, smelled wisteria. She went to the bathroom, came back and cried into Boone’s fur. She thought she’d worn herself out, but still she thrashed, the pillow too hot, her hair strangling her.

Sam snoring lightly, Boone running in a dream. She replayed the fox at the hammock, just letting Boone bark himself quiet. Boone never breaking through the electric fence they had cranked to its strongest level, the fence that kept him high on their hill, the fence he’d only broken through twice before, and never on the strongest setting. The fence one more so-called improvement.

Maybe some things never belonged anywhere.

Sunday morning, she waited until Sam finished his first cup of coffee. They sat outside on the patio, watching Boone roll on his back in the sunshine and grass. She said, “I want to do it ourselves.”

“Do what?” asked Sam, flicking dried bird poop off the arm of his chair.

“Take care of Boone,” said Laurel.

“We are.”

“I mean, we should do it.” She watched him sip his coffee, cock his head at her, understand.

Sam said, “We don’t know how.”

“Well, we know of ways . . .”

Sam flicked his eyes between hers. He still had sleep in the corner of his left eye, his hair flat on one side. He said, “Laurel, I don’t want to do that.”

“I don’t either, but it’s better than taking him to the vet’s. He shakes and gets so nervous.” She looked up at the hemlock, blinked back tears, waited for her voice to steady. She took a breath and said, “I’m thinking a knife or a gun.”

“Are you insane?”

“You don’t take him to the vet’s. You don’t know how scared he is. He’ll have to wear his muzzle. Right before they kill him.” She snorted her snot and yanked the tissue from her pocket, wet and raggy from the last bout of tears. “I can’t do that to him, too.”

He sighed, put down his coffee cup. “Laurel, you—we, have done everything we possibly could. Most people would have given up on him long ago, and—”

“And that’s what we should have done because now he killed a dog, a nice dog.”

They said nothing. A nuthatch flew to the birdfeeder. They watched as the bird took a seed, flew up the tree to eat it.

They were restless without the picnic, without anything to do but love Boone, couldn’t start any of the projects still waiting: painting and staining, replacing doors, cutting back choking vines. Sam sharpened his chainsaw. Laurel took Boone and her book outside. She helped the dog into the hammock as she always did, and he lay across her, his elbow jammed in her stomach. She didn’t read.

The day she and Sam had cleaned up the creek bank, it had felt good to be by the water. The stream was different of course, the water wafting a wet mineral smell unlike the heavy green smell of still water, the current rushing as opposed to the gentle lap of water at a boat or lakeside. But it was similar enough, a place that could make her smile just looking at it.

Boone scrambled off the hammock, barking and ripping two threads of skin from her thigh, and Laurel sprinted to stop him from breaking the fence. But he halted yards shy of the white flags marking the boundary, and he set to sniffing the grass.

That’s how it had been the first few months at the new house, every time she let him out, a worry. They’d done a ton of research, deciding on the electric fence because it stopped her brother’s beagles from chasing deer, something Boone could neither dig under nor jump over. The second attack, while they were still in Minneapolis: Boone hurdled over his fence to get to the spaniel. She vaulted the fence after him, but it took forever to force Boone’s jaws open.

They’d agreed to pay in installments; she’d been dropping off their last check to the owner’s mailbox when he came home. She blushed, sweated, asked how the dog was. The man smiled—all the owners so nice, part of what made it so awful, no one to be mad at but herself. He said, “Mickey’s a marine. That dog will outlive me.” She’d been glad, of course, but mostly just because it meant she could forgive Boone, could still love him, stupidly so.

At 5:00 they gave Boone his butcher bone, and they cracked beers. Sam asked her about work, a too obvious effort to take her mind off Boone. When they first moved to Pennsylvania, she’d been relieved to be free of the accounting office, of the smells of other people’s lunches, their constant sniffling, sad stories of marriages and kids gone bad. She thought she’d love working for herself in the quiet of their home unless she had a meeting with one of the four small companies she freelanced for. Many days it was good, but it was lonely in a way she hadn’t expected, but for Boone.

Laurel lit the grill and made salads. Sam seared the steaks and while the meat rested, she took utensils, napkins, salads and two fresh beers to the deck.

She came back to three plates of steak, one cut in bite-sized pieces. Sam said, “He can’t have anything to eat after midnight.”

“He can if we do it ourselves.”

“Oh, Laurel.”

On the deck, Sam told Boone to sit, and the dog dropped his bone. Sam put the plate down and said, “eat slowly.” Boone waited for Sam’s release. “Okay, Bud.”

Boone did eat more leisurely, maybe full from the bone. He licked the plate, and it thunked across the deck boards. He lay down at their feet and fell asleep. They ate dinner in silence except when Sam pointed out a great blue heron flying over the creek.

“I think I can do it,” said Laurel.

Sam turned to her, poised to ask what, then sighed. “There’s no reason to put yourself through that. I promise it’s going to be hard enough.”

“I don’t want him dying anywhere else. We brought him here.” She could smell the creek, trees, chlorophyll. She gulped her beer. Said it. “I can cut his throat. I’ve helped you butcher the deer.”

“But the deer are already dead. You don’t hunt with me because you don’t want to shoot them.”

“I’ve shot turkey and pheasant with you.”

“Which you always say is not the same."

“And neither is this.”

Laurel stared at Boone, sleeping. The white T on his head broader than it used to be, his tawny freckles fading.

When the dog psychologist came to their apartment after the second attack, along with a muzzle—both at the spaniel’s owner’s insistence, so they wouldn’t have to put Boone down—Laurel was made to give Boone’s history. Dr. Anderson’s glasses slid down his nose. He asked about early dog interaction, and she recounted Adrian’s golden retriever Bell biting Boone. Laurel should have been watching more closely, making sure Boone in his puppy zeal wasn’t angering sweet Bell; she knew Adrian wouldn’t protect his dog. Then, she’d thought it was just puppy behavior, thought Bell had taught Boone well.

Dr. Anderson asked, “What did you do while they fought? How did you stop them?” She didn’t need such clear blame. “Did you yell? Console him?” Laurel didn’t know the right answer. She hated the psychologist as he jotted his notes. “How did he react?” The doctor persisted until Sam stepped in. Dr. Anderson had sighed and said, “I can’t help if you won’t help yourself. It sounds like he’s a product of his environment.”

A red tail hawk screamed out of sight, and Laurel put her plate on the low, small table between their chairs. She sipped her beer. “I can’t use a gun.”

“Laurel,” he said, reaching for her hand, “please stop.”

“It will—”

“—Laurel,” Sam said to their interwoven fingers. “He will jerk. Spasm. Remember the turkey?” She knew which one he meant, her second tom. She’d shot low. The turkey only fled twenty yards. The hens scattered briefly, but they, too, watched the tom’s struggle. He’d clucked, flapped, and though they waited half an hour, still the bird wasn’t dead when they approached. The tom tried to flee, one wing broken, a leg too, leaves around him beaten. Sam dropped to his knees, corralled the bird, and sliced its throat. She had peed her pants a little.

On the deck, Laurel watched a bat dart in the leftover blue light of evening.

She said, “We have those pills from the move.” They’d asked their Minnesota vet for downers because Boone had been frantic about the boxes, the missing couch and chair they’d sold on Craigslist. “I’ll give him a dose an hour before.”

Sam shook his head, stacked their plates, and let the screen door slam behind him. Boone picked his head up, checked eyes with Laurel, then groaned as he lay back down.

Later, she came in, found Sam in the bedroom, his eyes full. “It’s going to be awful.”

She said, “It’s going to be awful either way.”

He got up, stalked to the door and called for Boone.

“Where are you going?”

“To dig the hole.”

Only Boone slept. At 6:00 a.m., Sam emailed his boss to say he was taking a sick day. Laurel made coffee, and Boone followed her around waiting for breakfast. She crushed two pills into a leftover burger and forked it into pieces. “Spoiled,” she said as he sat. “And loved,” she added as she pet his head, their own sign for him to release. The food was gone in seconds, and she let him outside. Already it was hot and muggy. Would hit 97.

When Laurel handed Sam a mug of coffee, his lips were white blue. Her stomach burned. In the basement she found his Buck knife. Back upstairs, she laid the knife on the counter. Sam stood at the door watching Boone sniff the base of a tree. She asked, “You hungry?”

Sam shook his head. She’d wait to call the vet’s office until she’d gone through with it. Maybe Sam would call John Pick. She took a sip of coffee; its acid singed, and she put her mug down. She walked outside towards Boone, and the cool dirt on her bare feet was a surprise and a relief. She lay down next to the dog, imagined calling John Pick herself, telling him Boone was dead while he snored at her feet. Maybe keep the appointment and just have Boone’s vocal cords cut.

When she came back inside after Boone was asleep, his breathing slow, steady, Sam’s eyes were red. He asked, “You’re sure?”

She picked up the knife.

He said, “Let’s get him close to the hole then.”

They had to walk on either side of Boone to keep him going, and they laughed bitterly when he lay down halfway to the top of the hill. They encouraged him as if he was learning to walk, and she thought they’d both gone mad. The hole, at the tree line just beyond the garden, was large enough that Boone’s legs could be fully extended. It wasn’t deep, but deep enough. She strangled out, “Thank you.”

Sam kneeled, straddled, and locked Boone between his knees. Laurel stared at him, her face draining. She’d imagined them sitting next to him, petting him. “Trust me,” Sam said, “It’s going to be better this way.” He kneed in tight to Boone, then fell forward over him, covering him, turtling him, letting out a groan so awful and raw, Laurel almost gave in.

She swiped her eyes with the back of her hand, then swabbed her nose with her fingers and wiped them on her shorts. She unlatched the knife, looked at Sam. He stared back.

She kneeled in front of Boone’s throat, white and thick, his favorite place to be scratched in these older years. In both hands, she took his big head, heavy with sleep, kissed him and rubbed her damp face into the folds of his ears. “Love you, Boone.” She sat back on her knees, moved forward.

Sam leaned over and choked, “Love you, Bud.” He pulled Boone’s jaw up to bare his neck and said, “You have to do it fast and hard, harder than you think.”

She bolted her jaw. She’d made Boone this way, ruined him

She jammed the knife into Boone’s throat, yanked, struck something hard and awful, and stopped: frozen. Boone convulsed, scrambled, wailed, bucked.

Sam jerked with Boone, then clenched his hand around Laurel’s on the blade’s handle. With the knife in their hands, they plunged.

Hours later, Boone buried, their clothes in the wash, Laurel couldn’t stand the house, couldn’t stand Boone’s bed, his toys.

She’d made the calls, offered for John Pick to come to the grave if he needed to. He said, “I have my own grave to visit,” and hung up. Josie was silent but apparently nodding by the scratching sound on the phone. A dog barked in the background, then Josie said, “Okay, hon. You take care.”

Laurel suggested the creek because they never took Boone there, too nervous they might meet another dog. They’d hunted rusty crayfish once last summer, boiled the crawdads, ate the sweet tails. They’d been drunk on their cause: killing invasives, helping the natives survive.

Thirty minutes into the hunt, Sam downstream, Laurel stepped and four crawdads burst around her, a kind of creepy firework. She took another step, then another, and each time crayfish pulsed away, settled, pulsed, settled. She swiped at them with her net, banged the rusties into the cooler, slammed the lid against their scrabbling sound.

Sam splashed to her with three crawfish in his net. She opened the cooler and said, “Damn invasives. Not a single native.”

“Not their fault they’re here.” Sam shook the crayfish free of the mesh, didn’t look at her.

Laurel considered, wanted him to be angry too. Wanted him to bang his net, scream at her for all she’d wrecked. She sneered, “Whose fault is it?”

Sam’s chest flushed. “Damn it, Laurel.” He smacked the cooler’s lid, spit when he said, “Boone’s not your fault.”

Her face seared.

She choked, “He’s a product of his environment.”

Sam hung his arms, net dangling into the creek. His voice, gravel, said, “He was a bad dog.” Sam shook his head, then took a breath. His words tumbled, “But a great bud.” He turned and lumbered back upstream.

Laurel blinked fast, kept her head to the current. In the shadows, a sunfish swam figure eights. It finned its circular bed, nests she knew well from her Minnesota lakes. A pumpkinseed, just like at home: lava-tipped gill plate, ecstatic blue lightning strikes at its face. Homesickness, a near burn, raced through her.

She stared up the creek at Sam, bent in his hunt: determined, bound. Watching him, quartz lodged in her throat. Then behind it, all the other shrapnel he had shown her since the move: beech nut hulls, deserted caddis cases, broken sycamore seed balls, half a bluebird egg— all the detritus of this new life in this new land.

She looked for the pumpkinseed: only saw the sunfish’s symmetrical nest—burnished pebbles of quartz and shale, polished tawny and ochre acorn-sized stones—the tended circle of the sunfish’s efforts: a vow

Heather E. Goodman’s fiction has been published in Gray’s Sporting Journal, Witness, Shenandoah, Crab Orchard Review, and The Chicago Tribune, where her story won the Nelson Algren Award. She teaches high school students and lives in a log cabin along a creek in Pennsylvania with her husband Paul and pooch Leo.