For thirty-six years Marcha was the leading Uruguayan weekly and one of the most important political publications in Latin America. It was closed down by the government last year, after a long political struggle which included repeated suspensions, fines, and, in 1974, the jailing of its editor-in-chief, assistant editor, two members of a literary jury which had awarded a prize to a short story about political tortures in Uruguay, and the author of the story. By the time, months later, that the journal was allowed to resume publication, all but the author having been set free, its back had been broken.

Founded in 1939, on the eve of World War II, Marcha was not only of decisive importance to the left—Che Guevara’s letter about the new revolutionary man, addressed to its editor, Carlos Quijano, was originally published there—but also instrumental in promoting the new literature. Marcha's first literary editor was Juan Carlos Onetti, who brought to its pages some of his favorite authors—Céline, Faulkner—and opened the magazine to a new generation of Uruguayan writers. In the fifties and sixties, Marcha became a truly Latin-American publication: the Guatemalan Miguel Angel Asturias and the Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, the Cuban Guillermo Cabrera Infante and the Argentine Julio Cortázar became contributors.

But it was mainly the River Plate writers who gave Marcha its unique flavor. To recapture now some of its tone and style, I have selected five short stories published during its most pioneering times. These make up only a sample of what was printed year after year in a weekly that represented Latin-American culture at its best.

The spirit that made Marcha possible is gone. Of the four Uruguayan writers in this selection, only Carlos Martínez Moreno still lives and works in Uruguay; Felisberto Hernández died in 1962, and the other two live in exile: Onetti in Madrid and Benedetti in Cuba. On the other bank of the River Plate, a new Perón government has come and gone, leaving both Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares as incredible survivors of a canceled time. What remains of the days when the stories were first printed are the texts now especially translated for Fiction. They are witness to what was once an original culture.

"Monsterfest" (La fiesta del monstruo) is the product of the joint effort of Jorge Luis Borges (born in 1899) and his friend and disciple Adolfo Bioy Casares (born in 1914). It is a cruel parody of Argentina at the time of Perón's first government, when anti-Semitism was rampant (the Nazis were still fighting in Europe and the Argentine government hadn't made up its mind about who was going to win). For quite a long time, the story circulated underground in Buenos Aires, slimly protected by the pseudonym, H. Bustos Domecq, which both authors used for their detective stories. It was first published in Marcha in 1955, in the aftermath of Perón's downfall. Using a baroque language that stretches savagely the rather mild River Plate slang, Borges and Bioy (or Biorges, as I call them) criticized the corruption and brutality which was then commonplace in Argentina. The story and its very language do not attempt to represent realistically any specific historical moment in Argentina but to symbolize the underlying grotesque reality.

"The Crocodile" (El cocodrilo) is typical of Felisberto Hernández's fumbling, absentminded by highly comical style. Born in Uruguay in 1902, Felisberto (as he was always called) combined a truly surrealist imagination with a perhaps too colloquial speech to produce small masterpieces about the horrors and hazards of everyday life.

“María Bonita” was originally published in Marcha as a short story about the dramatic arrival of a small band of prostitutes to a sleepy and imaginary village on the bank of the River Plate, but it was actually an excerpt of the first version of Juan Carlos Onetti’s most important novel, Junta, the Bodysnatcher (published in book form in 1964). The novel told its tale of Gothic horror and laughter in a very elaborate way, alternating the narrative points of view of the main character, Junta, the owner of the local brothel, and the townspeople, its shocked and voyeuristic costumers. For this selection, the final version of the novel has been preferred to the original text printed in Marcha. Onetti (born in 1909) was then living in Buenos Aires and created the sleepy town of Santa María, where the story and the novel are located, out of fragments of Montevideo and Buenos Aires.

“The Wreath on the Door” (El lazo en la aldaba) is a brilliant exercise in satire. Layer upon layer of Uruguayan gentility are revealed in a story which appears to be concerned only with the sad and comic fate of a not too respected nor respectable mother. A lawyer by profession, Carlos Martínez Moreno (born in 1917) brings to literature a lucid, implacable eye.

“The Iriartes” (Familia Iriarte) attacks frontally some of the myths of bureaucracy (machismo is here shown as a deplorable form of the rat race) but the text never forgets to laugh at its own indignation. The author, as much as the characters and readers, is involved in the same reality. The most successful of all Uruguayan writers, Mario Benedetti (born in 1920) has had some of his stories and novels filmed or adapted for television in Argentina.

Emir Rodriguez Monegal

• • • • •

Emir Rodríguez Monegal teaches Latin-American literature at Yale University. For seventeen years he edited Marcha's literary pages. He is the author of the Borzoi Anthology of Latin-American Literature to be published by Knopf next spring.

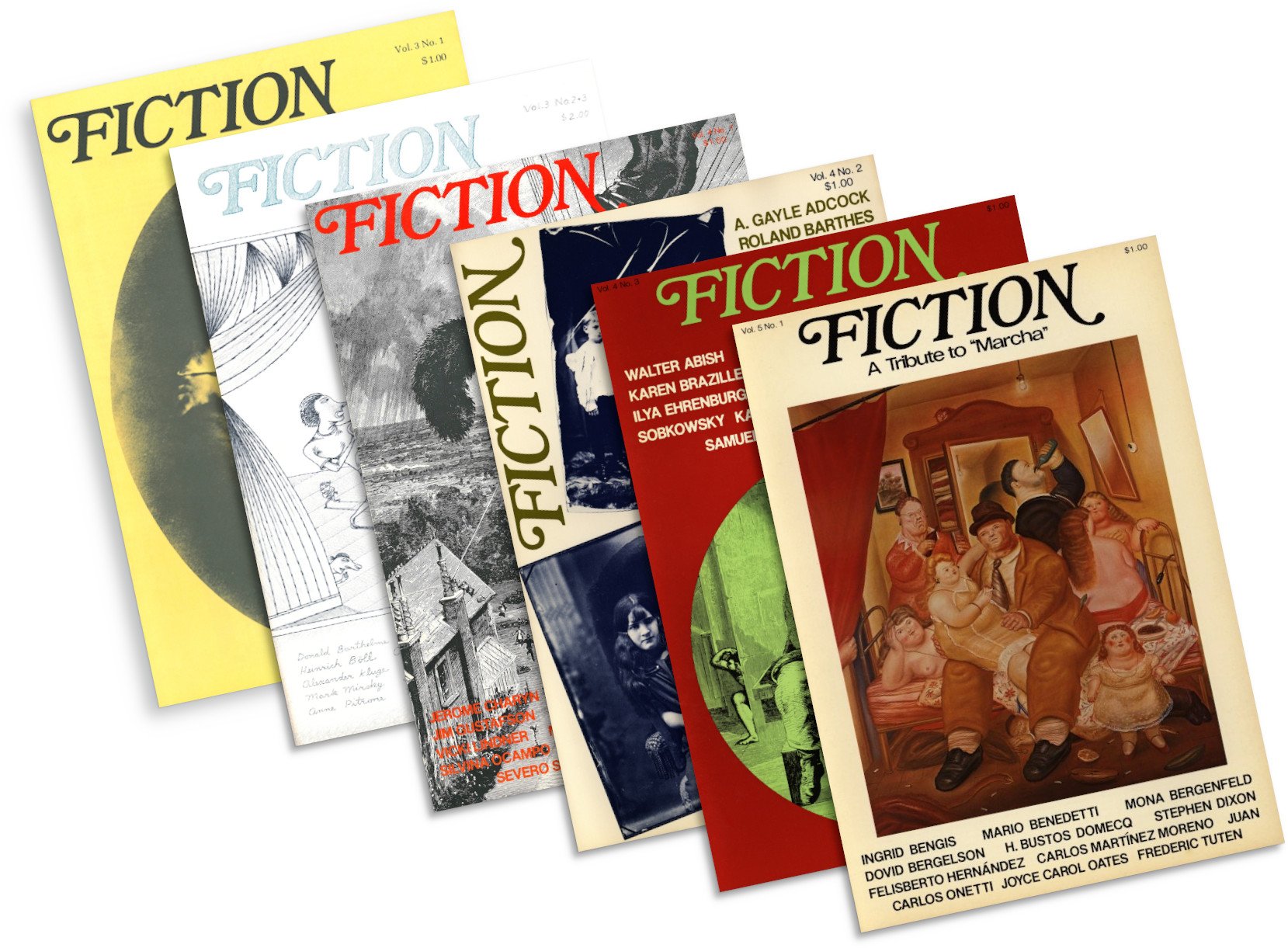

Price: $67

All 6 large “piano sheet sized” issues (10″ x 14″)

Published: 1974 - 1976