Foreword

by Leah Kogen-Elimeliah

November21, 2023

For Sara Ludy, an American artist from Bluemont, a town in rural Virginia near the Appalachian Trail, the unknown, the unseen, and the ghostlike are what drives her creativity to those shadowy and unfamiliar territories. This is where questions and what she refers to as paranormal experiences, help gauge her sense of belonging while getting inside the virtual and the metaphysical worlds, touching on what Sara regards as “energy” that produces and shapes her works of art.

I sat down with Sara last December, via Zoom, to talk about her creative process and what being an artist in the digital age means to her. Composed, mindful, and contemplative, Sara took me into her universe, delving into the personal and the imaginative while exploring meaning inside and outside her own work.

Sara grew up playing music and watching her father, an artist and “brilliant draftsman,” and Bob Ross, “who was always on TV,” draw and make art. She is now a composer and works in multiple mediums, such as digital painting, animation, VR, websites, installation, and sound. Her work is often a hybrid of augmented and virtual reality, depicting spaces and objects with simulated manipulation, looking for ways to interpret the immaterial and the unseen while also focusing on the in-between spaces and time, both in the physical and the virtual world. When I asked her how she began her career as an artist, her response was illuminating. “Where I grew up, the whole area was full of ghost stories, and it was spoken of very casually, so I always liked the idea of the unseen and the mystery of the paranormal, how things exist underneath and beyond what we experience on a day to day. I still love all things paranormal and that interest led me to be interested in cosmology and the philosophy of consciousness.”

What Sara’s artwork highlights is that ultimately we cannot escape our ceaseless desire and need to know and understand the mysteries of the universe, and even ourselves because as human beings we possess an innate inclination to unravel the mysteries of the unknown. For example, some of us, including myself, are uneasy with the irreversible advancement of technology and the fragmented world it has created, particularly with the rise of social media, NFT's, metaverse, Roblox and other such platforms. This persistence to advance, to discover something no one has discovered, makes me think that humanity finds itself in a pressing race against time, driven by a shared sense of urgency. We stand at the precipice, keenly aware that the end may be looming, with an apocalyptic mindset, and thus we strive to propel ourselves into the future with unwavering determination.

James Bridle, a writer and artist points out in his article, “Rise of the machines: has technology evolved beyond our control?” that, “Something strange has happened to our way of thinking – and as a result, even stranger things are happening to the world. We have come to believe that everything is computable and can be resolved by the application of new technologies … they extend beyond the boundaries … they exceed the understanding of even their creators.”

This relentless pursuit towards the unknown often places us in competition with the very technological advancements we have brought forth, advancements that constantly push the boundaries of our capabilities, even as we grapple with apprehension and weariness. It is within these uncharted territories that we catch a glimpse of both the possibilities and limitations that lie within our potential.

Bridle continues, “As a result, we understand less and less about the world as these powerful technologies assume more control over our everyday lives … Instead of a utopian future in which technological advancement casts a dazzling, emancipatory light on the world, we seem to be entering a new dark age characterized by ever more bizarre and unforeseen events.” Therefore, we find ourselves immersed in a tangible struggle, driven by a collective need to navigate uncharted frontiers, and to confront the profound shifts unfolding around us. The urgency of our time demands that we fortify our resolve, while maintaining a steadfast commitment to harnessing the power of progress, innovation, and the enduring human spirit.

Sara’s work does just that, producing a kind of energy within the interior of her digital art incorporating surreal and abstract elements, mixing real and the imagined. Her compositions reflect fantasy driven motifs that also seem familiar. She presents us with a visual spin of dreamy, naturalistic worlds combined with futuristic aspects and geographical and architectural landscapes. Minimalist yet complex, her works resemble a kind of universe perhaps we wish we had, one that didn’t need so much unpacking.

Sara Ludy

An Interview

with Leah Kogen-Elimeliah

Leah Elimeliah: Can you talk about your childhood and how you fell into art? Were you always interested in digital art and animation?

Sara Ludy: I grew up in the ’80s, pre-internet, and spent half of my time outside, the other half in front of a television playing video games, watching cartoons, movies, or sci-fi shows. I also loved how-to [PBS] shows like The Joy of Painting and Yan Can Cook. Bob Ross catalyzed my interest in painting, while my parents being big music lovers inspired me to have a deep appreciation for music. I lived far away from other kids, so I spent a lot of time entertaining myself. I loved world building and going inward. Living in a rural area taught me a lot about nature and contemplation. All these things became lenses through which I see the world.

My Grandmother had this old UHF/VHF television in the basement that I preferred playing Castlevania on because the TV felt alive and a bit scary, the images would be ghostlike when transitioning from one scene to the next, the buzzing sound would change pitch depending on what was displayed on the screen. It just made sense for that game, and I didn’t understand why at the time, but [I] loved feeling and hearing the buzz, the light of screens, its physicality. Even after you turned off these old televisions there would be a point of light, or even afterimages that would take forever to disappear. In hindsight, this definitely has influenced a lot of my work, finding the presence of things, the hums and energies.

Although I started making MacPaint drawings and collages in Photoshop in high school, I didn’t know new media art existed until I went to [the School of the Art Institute of Chicago]. Immediately, when I learned about it, I wanted to work with media and its materiality, its hardware and presence. I started with analog media—video, film, ¼" tape—and eventually fell in love with digital art when taking a net art class in 2001, taught by Jon Cates. I was working with a lot of different media at the time, and this led me to an interdisciplinary practice.

Leah: Can you talk a bit about mixing artistic mediums and genres? There is richness in that process.

Sara: It’s second nature at this point. I want to get as close to material as possible, until something interesting happens. I send materials through different programs, weave them in and out of different processes until they’re transformed into something that feels right. It’s all very intuitive, it’s about extracting an energy, a new perspective, collapsing dimensional entities.

Leah: Abstract art has taken a new form through digital and augmented reality. What can you say on that subject, and how does it fit into your work?

Sara: Abstraction, to me, is a condition or state of an idea or object that can just as easily be seen as representational. It’s our perception and everything we bring to something that allows us to view it in a particular way. Things can be simultaneously abstract and representative of something and they can also oscillate between the two. It depends on how ideas and aesthetics are embedded in something and how one will derive meaning. I don’t consciously make “abstract work”. I abstract things, but I’m not [setting] out to make abstraction. If anything, I’m trying to make sense out of abstraction and turn it into something more readable, even if it’s subtle, something that gives a sense of space and depth and place. Pure abstraction is not my interest right now, but perhaps one day I will entertain it.

Leah: Can you tell me about Dream House and its “animistics” elements? I really loved this piece because it feels like your work lives in two different worlds and you have opened up their gates. How do you feel about still images that come from your longer pieces?

Sara: Animistics are these 3D objects that I made for Dream House, which is a 3D model that’s a recreation of several different dreams I’ve had, some recurring and others lucid. I was curious about what it would be like to model this dream space and did it as a sort of hobby. When I started modeling the architecture, other past dream spaces came to mind and the architecture became a hybrid dream space.

The first lucid dream I ever had was so life-changing and so profound that it made me question everything I knew. I wanted to understand what I experienced and started reading lots on quantum physics so I could understand more about fundamental aspects of reality. In one dream, I had a friend who passed away and we ended up hugging in this other realm and it was as real as anything. I was having a spiritual awakening through dreams and science.

Animistics were created with the idea in mind that one day they would turn into interactive objects in VR, such as Cabbage Head (Energy Sponge) being a sort of barometer for different energies. I printed these on aluminum for my solo exhibition, Subsurface Hell, at bitforms gallery in 2016 and haven’t printed any since. In general, I don’t print much. I appreciate digital material as it is and, if anything, I’m waiting for technology to catch up so I can display static images more easily.

Leah: Translating a dream into an architectural space, this is all so fascinating. What’s your ideal virtual environment? Do people tread between the real and the virtual, or do you feel like it's fluid and we can flow in and out of each one?

Sara: Yeah, it's all fluid, it's all continuous, it's all existing. What I like about virtual space is how it can be all-encompassing, how it can collapse multiple mediums and dimensions into one and how it allows you to think and play with space and time in different ways. You don’t have to adhere to real world architectural constraints, you can alter gravity and physics through simulation.

For several years, I worked as an interior designer at Commune Design in LA, and my job was to design spaces from concept to construction and all the in-between. When I left to focus on art full time, I wanted to experiment with what architecture could be when it’s intuitively approached, not from a design intention. Dream House was built in a manner that utilized my understanding of real-world architecture while also providing a context where I could freely explore different architectural forms without the constraints of it being physical.

Leah: Do you feel that the space you virtually create is closer to the subconscious, whereas if you create something like a sculpture or painting, it’s more grounded and tangible?

Sara: Not really. I think sculpture, painting, performance, digital media, any medium can access the subconscious equally and I don’t find one or the other to be more tangible in its qualities. I think of tangibility as being perceptual. But I do like creating with digital media because working with illuminated imagery is similar to dreams and imagined imagery.

Leah: You mentioned you played video games as a kid and, while looking through some of your video projects, it felt like the interior of a game world. How would these rooms in virtual space translate into real space? Did you ever think of physically creating them?

Sara: I’m grateful I grew up playing 8-bit video games, it gave me a deep appreciation for how easily you can be transported into a virtual space with limited graphics. I loved dreaming inside virtual spaces that were minimal. They used similar visual vocabularies and sound effects, but they were all so incredibly different, with their own logic and atmosphere. Each felt special. If I were to translate a virtual space into something material, I would consider how to create something with a minimal gesture, that maybe didn’t require a bunch of resources to be built, but I don't know what that would look like, I would need to know the context in which it would exist.

Leah: Can you talk a bit about your Tumbleweeds project and how you connected technology to nature, touching on the simplicity and complexity of the project and its process?

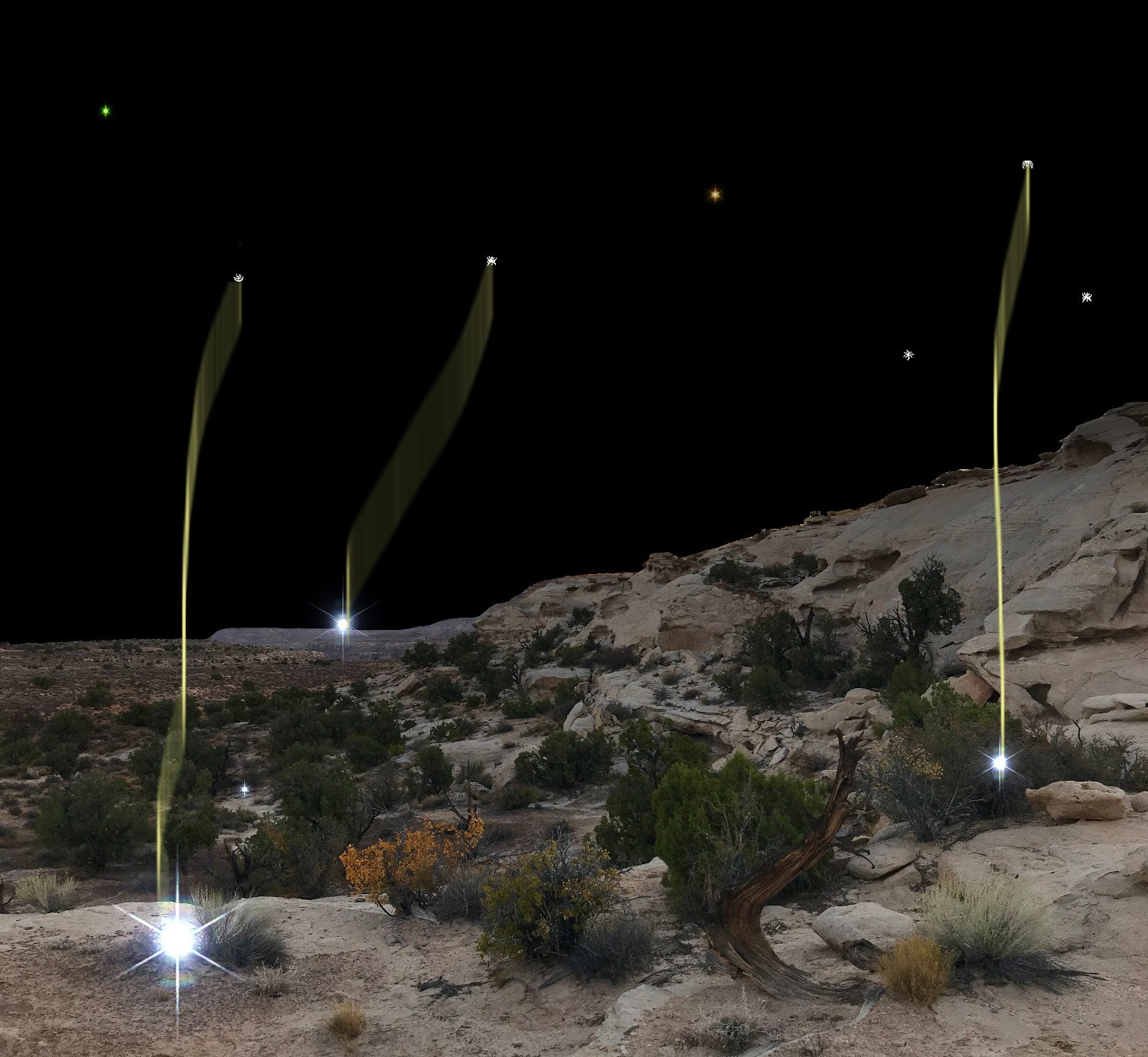

Sara: Tumbleweeds is part of a series called Sunrise/Sunset at the Whitney Museum, which invites artists to make web interventions. The limitations given are that the piece will only be visible for 30 seconds, two times a day, at sunrise and sunset, New York time. I started thinking about ways to expand that 30 second integer of time and decided to expand the media beyond the browser through a sculpture and ended up with a piece about light through space and time.

The sculpture is a land sculpture made of tumbleweeds, found glass, and biodegradable garden twine. I started tying pieces of found glass to the center of tumbleweeds so that when they are carried by wind, they generate light patterns and when there’s several spread out anywhere from 10 feet to 10 miles, it creates this expansive, yet lightweight and temporary structure that light can reflect from across an expansive space. The garden twine degrades after a few months and all the materials fall back to the desert where they came from. No one ever really sees this sculpture and I don’t even get to see this sculpture in all its forms, its timeline and history is generated by wind.

The only part of the sculpture that is visible is through an animated star map that contains captured reflections of the found pieces of glass. As more tumbleweeds are fitted with glass, the star map grows and changes, representing the ephemeral nature of the unseen land sculpture.

Leah: What I found interesting is the intentionality in connecting the natural with the technological, the fabrication of it. I am curious to know what is the connection and the exploration that you are trying to bring forward with this creation?

Sara: At the time I was working on this piece I was burned out from being online so much during the pandemic that I started making sculptures in my garden and painting again. I wanted to find a way to make a piece that wasn’t so heavy in tech and animated GIFs seemed perfect, they represent something essential and universal and a part of internet cosmology. I didn’t want to entertain anything about Web 3.0 or Blockchain, even though that’s what was in the general sphere at the time. I wanted the work to slow down, honor the time we were in and point towards the space between hyper-connection and hyper-isolation we had been existing in.

When I decided to expand the browser work as a land sculpture, I wanted the material parts to be as lightweight as the animated GIFs and I ended up choosing tumbleweeds, found glass, and biodegradable twine. They became lightweight frameworks through which the lightest material could be explored: light itself.

Leah: About a year ago I had the pleasure of sitting down with Terry Fugate-Wilcox, a minimalist and natural-process post-minimalist, an Actual artist painter from the ’70s and ’80s whose ideas about art are similar to yours. One of the things he focused on was the concept that time and natural processes should be able to change art's appearance, and in some cases, art pieces will potentially disintegrate. It’s about how an artist relinquishes control of his work to nature and lets nature take its course. Art that doesn't impose on nature. Which also means that it’s not about commodifying and getting rich off the art.

Sara: I love thinking about long timescales and I am generally OK with things disintegrating, that’s what nature does and that’s what nature will inevitably do a lot of in our lifetime. Ideas are something that can last and are worth preserving and they don’t necessarily need a lot of material weight to exist. I like thinking about the far out idea of information already being preserved on a quantum level. If so, will we one day have direct access to this information, perhaps through a state of consciousness or something even more immediate? Most of us have experienced times where information or synchronicities show up all of a sudden. I have a hard time ignoring, and wish not to ignore, these “anomalies” in context of what we consider to be “real.”

Leah: What do you think of the new AI art and all its capabilities? Do you see it as a threat or a tool for your art?

Sara: I can see how some might see AI-generated art as a threat to their craft. I am not threatened by it in a creative sense, but I’m also not incredibly optimistic about where it will go.

I recently had a dream where an Evangelical AI oracle was being broadcasted on TV 24/7, and people worshiped this AI and only “chosen” people could ask the oracle questions. A new religion was formed and the goodness of people were determined by this entity. This very well could have been a book or movie I’ve experienced being rehashed, but it was eerie. New technologies have the ability to expand our understanding, but they also have the ability to contract it. With that [said], I have been dabbling in AI for over a year now, but it’s still just a sliver of my practice, and I’m treading it with cautious optimism.

Leah: How do you combine culture into your data that forms or infuses your art and behavior of what you create and what influences it?

Sara: I like to say that if my work is holding a double-sided mirror to the world, it’s pointed towards the cosmos and Earth, but slightly tilted so culture, mostly internet culture, can ambiently filter through. I’m not interested in making work that directly points to “the times.” I like art that operates in different spheres, outside of art world trends, outside of the market… art that is made out of necessity and curiosity, with lots of unknowingness and also a bit messy. When art becomes formulaic, where ideas and form are perfectly packaged together to illustrate or “say something,” it’s painfully boring. They act like products at that point. I want to push boundaries and do things differently and create space for new ways of seeing and also support artists who do the same. I’d rather fail a thousand times doing different things than make something easy and saleable. Art is a space for transcendence. I’m very protective of that.

Leah: It seems like a lot of your work also connects to memory. How do you combine memory into your data?

Sara: Aside from Dream House, where I used memory in a very direct way, memory is used as an intuitive tool and is mostly coming from a very somatic place. Experiences and feelings are embedded in our bodies and nervous systems and when working on something it seemingly lifts out of these parts of my body. When I’m in a super flow state while working I forget to breathe, or sometimes I get a feeling of energy rising through my spine. These are signals telling me I’m on the right path. It’s like my body knows before my logic mind does. Unconsciously, amorphous body-like forms do appear in my work.

But even more than memory, I’m interested in the sort of precognitive states I find myself in, those too rise out of my body in the same way. I know when I’m making something good, when I’m onto something, and most of the time I believe these works are meant to be understood years later. One work I made in 2019 was seemingly a premonition of 2020. Its final title is Dusk, but throughout the making of it I called it Dark World, named after the Dark World in The Legend of Zelda, which is a parallel dimension in Hyrule where everything is much darker.

In Dusk, a woman is holding a wand with bubbles floating towards an amorphous virus-like shape, and she is wearing a mask. At the time, my logic mind was telling me to get rid of the mask, I didn’t want it to be misinterpreted. But my gut was telling me to leave it. It was an odd piece. I typically don't have humans in my work, let alone wearing a mask.

Leah: So what do you think about the metaverse?

Sara: I’m not excited about the idea of a “global metaverse” when one third of the population doesn’t have access to the internet, nor am I excited about an even more immersive social space.

Leah: Lastly, the big question: Where do you think the world is going? How do you think people move through these virtual territories?

Sara: Right now I’m more concerned about the state of our planet than thinking about the future of virtual space. I think more about what it will mean to navigate physical territories in the future when the climate becomes even more unpredictable. We really need to slow down and stop outpacing ourselves.

Sara Ludy (b. 1980, Orange, CA) is an American artist and composer working in a wide range of media, including painting, AI, VR, video, photography, websites, installation, and sound. Through an interdisciplinary practice, hybrid forms emerge from the confluence of nature and simulation to explore notions of immateriality and being. Previous exhibitions of Ludy’s work include the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Vancouver Art Gallery, Whitney Museum of American Art, Berkeley Art Museum, and Künstlerhaus Bethanien. Her work has been featured in Modern Painters, The New York Times, Art Forum, Art in America, and Cultured Magazine. Sara lives and works in Placitas, New Mexico.